| (Clicking

on the thumbnail images will launch a new window and a larger version

of the thumbnail.) |

| Last updated: March 21, 2007. |

Crocuta crocuta

Order: Carnivora

Family: Hyaenidae

1) General Zoological Data

The Hyaenidae are a Miocene offshoot from the Viverridae , representing features of African civets (Gregory & Hellman, 1939). There are a numerous paleontological studies of the many formerly existing hyena species; some of these are summarized in the modern phylogenetic study by Koepfli et al. (2006). These authors studied a variety of genes, determined that the related aardwolf probably split last, and have tight results for their genetic analysis. This hyena species is widely distributed through Africa but was even more widely represented to the end of the Pleistocene in Europe and Asia . A well-known breeding colony exists in Berkeley , California where most of the endocrine and reproductive studies have been conducted. The longevity of a spotted hyena was given as being up to 41 years by Weigl (2005), but a majority probably reaches a life span of only around thirty years. The animal's name may derive from crocus , Latin for the color of saffron (as there is a slightly yellow skin coloration; but Gotch (1979) draws attention to a rare Latin word crocuta as meaning ‘an unknown animal from Ethiopia '. The animals weigh around 40-60 kg, with females being somewhat larger. The most remarkable feature of spotted hyenas is the presence of what appears to be a penis present in both sexes (Neaves et al., 1980) which has made assignment of sex difficult initially. In a beautifully illustrated paper by Künkel (2002) the point was made that Aristotle believed that the animal was ‘hermaphroditic' because of this genital feature. Chromosome as well as Barr body studies, and examination of specific RFLPs have now enabled rapid sex determination (Schwerin & Pitra, 1994).

|

Spotted hyena at San Diego Zoo's Wild Animal Park. |

2) General Gestational Data

The length of gestation is +/- 110 days, the estrous cycle is 14 days. One to three young develop (1.5 kg) and there is fierce competition among the neonatal littermates (Nowak, 1999). During pregnancy the female has high circulating androgen levels that are needed for normal male mounting procedures, but modifying the fetal female external genital system sufficiently to make first births difficult and costly (Licht et al., 1998; Drea et al., 1998; Glickman et al., 1998; Drea et al., 2002). The difficulty of determining fetal age was solved by the study of Place et al. (2002) who did serial sonography and found that femur length was the most accurate datum to be assessed.

3) Implantation

The youngest specimen so far studied was of a 45 days old gestation; it still had a yolk sac (Wynn & Amoroso, 1964). No really early implantation stages have apparently been studied.

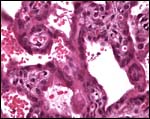

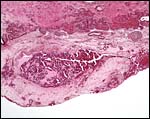

4) General Characterization of the Placenta

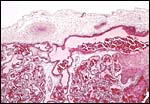

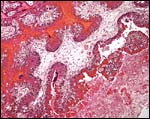

A term placenta was described by Morton (1957) in a multigravid female. The fetus was 27 cm long and the placenta was 40 cm in circumference and varied in width from 8.5 to 11 cm. It was 1.4 cm thick. It was blue and had no marginal color change. Several stages of development were available to Wynn & Amoroso (1964). Among carnivores, this placenta is unique in not being endotheliochorial but being hemochorial (Enders et al., 2006). This is an annular villous hemochorial placenta with occasional interruption of the circular shape (see Wynn & Amoroso, 1964).Often, two lobes of the zonary placenta are observed and in one placenta described by Wynn & Amoroso (1964), these lobes measured 8.5x5.3x1.6 cm each. No placental weight has been provided in any reference. The villi anastomose and make a labyrinthine structure, especially in the midportions of the placenta.

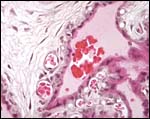

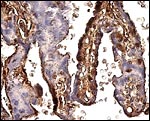

5) Details of fetal/maternal barrier

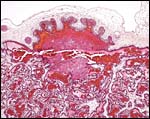

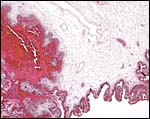

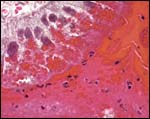

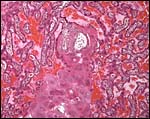

Wynn et al. (1990) studied the placenta with antibodies to vimentin and cytokeratin and showed the interhemal ‘barrier' to be monohemochorial, rather than endotheliochorial as was once suspected to be the case; this is further confirmed by the study of Enders et al. (2006) who considered this to be unusual for carnivores with their usually endotheliochorial placentations. There is a discontinuous cytotrophoblastic region overlain by syncytiotrophoblast, also shown in the electronmicroscopic study by Oduor-Okelo & Neaves (1982). The hyena placenta presents a number of unusual features that have been delineated by Enders et al. (2006). Their interest has mainly focused on the absorptive features of the trophoblast and they showed that there is extensive phagocytosis of red blood cells in several areas beneath the chorionic surface and at the margin, in addition to endogenous lipid. Their interest has mainly focused on the absorptive features of the trophoblast and they showed that there is extensive phagocytosis of red blood cells and fat in several areas beneath the chorionic surface and at the margin. They likened the latter region to the green periphery of the dog placenta and they demonstrated not only the phagocytosis of maternal red blood cells but also fat; moreover, iron deposits were demonstrated with a Perl stain. The presence of much iron pigment had already been demonstrated by Morton (1957); my experience with the stain is a little different; in the preparations I investigated there was very little iron pigment present and it was confined mostly to the decidual tissue of the junctional zone. The subchorionic trophoblast and that on the tips of the villi at the ‘junctional zone' are unusually tall and cylindrical, engaging actively in phagocytosis. The trophoblastic tips of those basal villi stain heavily with cytokeratin antibodies and with lectins, as Enders et al. (2006) demonstrated beautifully. Instead of merely calling these regions of phagocytosis the ‘hemophagous zones', they refer to the tall columnar trophoblast as belonging to as ‘heterophagous region'. Others have drawn attention to the fact that the fetal capillaries are often within the syncytium and bulge upon its surface.

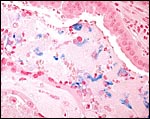

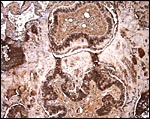

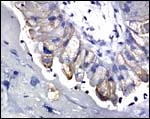

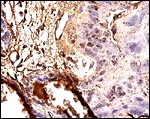

Enders et al. (2006) employed a mouse monoclonal cytokeratin antibody that was not available to me; rather, I used a pancytokeratin stain to delineate the next few photographs. It stained many more elements deeply but also, it is evident from these pictures just how irregularly cytokeratin-positive cells are distributed through the labyrinth and the junctional zone. Even the apparently absorptive tall columnar trophoblast had positive and negative areas, presumably defining regions that are more or less actively engaged in hemophagia.

When using a cytokeratin 19 antibody (skin), only a few of the tall trophoblastic tips were stained and none of the junctional zone decidual elements.

|

Cytokeratin 19 stain of trophoblast at junctional zone. |

6) Umbilical cord

The umbilical cord contains two arteries, two veins and the patent allantoic duct; it was 5-6 cm long in the term gestations described by Wynn & Amoroso (1964) and Morton (1957). In addition to the allantoic vessels there are smaller vitelline vessels. The cord is covered by amnionic epithelium.

7) Uteroplacental circulation

Morton (1957) reported the presence of maternal septa that carry large maternal blood vessels. The septa divide placental tissue and penetrate to the chorionic plate. Similarly, the in situ preparations of Wynn & Amoroso (1964) demonstrated that maternal blood enters directly into the intervillous space from endometrial arterial extensions and arrives under the chorionic plate whence it is distributed throughout the labyrinth.

8) Extraplacental membranes

The amnion fuses completely to the large vascularized allantoic membrane and to the surface of the umbilical cord. Morton (1957) reported from viewing the intact uterus of a term gestation that there 500 ml amnionic fluid and even more allantoic fluid within the respective sacs.

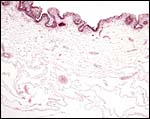

|

The free membranes are composed of loose connective tissue with allantoic vessels. |

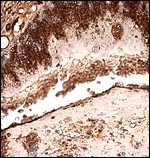

9) Trophoblast external to barrier

Wynn & Amoroso (1964) described in some detail the superficial infiltration of syncytiotrophoblast into the degenerating basal endometrium. They liken some of this endometrial debris to decidua of mares and are unclear as to the nature of some of the larger symplastic cells at the base but apparently no true decidua is being formed, although Enders et al. (2006) interpreted some of the clusters of large cells at the base as being decidua (see figure above). Deeper infiltration of trophoblast into the uterus does not occur.

|

A portion of junctional zone stained with pancytokeratin showing little staining of trophoblast and virtually none of the decidual cells. |

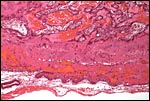

10) Endometrium

The uterus is bicornuate and has been well demonstrated in the illustrations by Wynn & Amoroso (1964). The reproductive tract of spotted hyenas is described in detail by Matthews (1939). The endometrial glands of the empty horn and even more of the placental horn show marked dilatation and abundant development (see Wynn & Amoroso, 1964) who illustrated this well. In later pregnancy the endometrium degenerates and is shed except for the bottom portions of the glands.

11) Various features

The social structure and hunting behaviors of spotted hyenas has been the topic of numerous interesting studies; access to these is provided in references to Nowak (1999). Likewise, the powerful dental structures and bite are oft-studied features. Vocal recognition studies were done by Holekamp et al. (1999) and they were compared with those occurring in vervet monkeys.

12) Endocrinology

Mossman & Duke (1973) and Matthews (1939) described the ovarian bursa, the fact that the cortex is thin, and that there is a large quantity of interstitial gland tissue. Dloniak et al. (2004) studied fecal androgen content in captive and wild spotted hyenas by HPLC before and after LHRH injections. Androgens rose several days after the stimulus, was higher in pregnant that lactating females and in ‘immigrant' males than ‘natal' males. Higher-ranking females had higher levels of androgens during pregnancy than lower-ranking ones; moreover, their neonates also showed more aggression after birth (Dloniak et al., 2006). The fetal androgen exposure through maternal circulating and elevated testosterone levels (some at least is produced by the placenta) has been widely studied; access to this literature is gained through: Licht et al., 1992; 1998; Drea et al., 1998; Glickman et al., 1998; Drea et al., 2002.

13) Genetics

Spotted hyenas have 40 chromosomes, very similar to those of the other members of hyenidae (Wurster et al. 1968; 1970); banding studies were done by her in 1982. More recently, Nash (O'Brien et al., 2006) has published a more refined banded karyotype. No hybridization with other hyenas has been reported. A characteristic ‘carnivore chromosome' with satellites is shown as # 10 below. Perelman et al. (2005) have compared ‘painting probes' of this species and compared it to a variety of others in order to arrive at the ‘original carnivore karyotype'. Most recently, Koepfli et al. (2006) have studied mtDNA and nuclear genes to secure the phylogenetic placement of the species. Vassetzky & Kramerov (2002) have directed attention to the ubiquitous presence of retroposons in carnivore, including the hyenas.

|

Karyotypes of spotted hyenas from Hsu & Benirschke, 1968. |

14) Immunology

I am not aware of any relevant studies.

15) Pathological features

Nobel et al. (1983) described a widely metastatic lymphosarcoma in an animal. A significant outbreak of streptococcal infection has been reported from the population in the Ngorongoro Crater (Honer et al., 2006). The organism was a subspecies of S. equi ; it was also identified in a carrier state and, of course, from sympatric Equus burchelli . In a hyena population from Serengeti, East et al. (2004) identified antibodies to coronavirus and even isolated it from some juvenile stool samples; it had – at most – some minor pathogenicity such as diarrhea.

16) Physiologic data

The most remarkable features (phallus in both sexes) has been studied innumerable times, beginning with detailed examination and measurements by Neaves et al. (1980). Griner (1983) mentions the presence of a baculum in males. Glickman et al. (2006) have recently summarized all information available on this phallic development in the female genital tract and concluded that it is ‘androgen-independent' (see also Licht et al., 1998). The unusual ‘phallic flipping' at mating was described in detail by Cunha et al. (2003). Moreover, the same group (Browne et al., 2006) showed with elaborate endocrine profiles that despite the fact that embryonic ovaries are capable of secreting androgens, this faculty does not begin until after the phallic development has already been completed in the female fetus (Cunha et al., 2005).

17) Other resources

Fibroblast cell strains are stored at CRES of the Zoological Society of San Diego and can be made available by contacting Dr. Oliver Ryder at oryder@ucsd.edu .

18) Other remarks – What additional Information is needed?

There is little information on really early stages of placental development and implantation. The weight of a term placenta has not been determined.

Acknowledgement

The sections of placenta were kindly donated by Dr. Allen Enders, Davis , CA . The animal photograph in this chapter comes from the Zoological Society of San Diego .

References

Browne, P., Place, N.J., Vidal, J.D., Moore , I.T., Cunha, G.R., Glickman, S.E. and Conley, A.J.: Endocrine differentiation of fetal ovaries and testes of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta): timing of androgen-independent versus androgen-driven genital development. Reproduction 132:649-659, 2006.

Cunha, G.R., Wang, Y., Place, N.J., Liu, W., Baskin, L. and Glickman, S.E.: Urogenital system of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben): a functional histological study. J. Morphol. 256:205-218, 2003.

Cunha, G.R., Place, N.J., Baskin, L., Conley, A., Weldele, M., Cunha, T.J., Wang, Y.Z., Cao, M. and Glickman, S.E.: The ontogeny of the urogenital system of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben). Biol. Reprod. 73:554-564, 2005.

Dloniak, S.M., French, J.A., Place, N.J., Weldele, M.L., Glickman, S.E. and Holekamp, K.E.: Non-invasive monitoring of fecal androgens in spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 135:51-61, 2004.

Dloniak, S.M., French, J.A. and Holekamp, K.E.: Rank-specific maternal effects of androgens in behaviour in wild spotted hyaenas. Nature 440:1190-1193, 2006.

Drea, C.M., Weldele, M.L., Forger, N.G., Coscia, E.M., Frank, L.G., Licht, P. and Glickman, S.E.: Androgens and masculinization of genitalia in the spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta). 2. Effects of prenatal anti-androgens. J. Reprod. Fertil. 113:117-127, 1998.

Drea, C.M., Place, N.J., Weldele, M.L., Coscia, E.M., Licht, P. and Glickman, S.E.: Exposure to naturally circulating androgens during foetal life incurs direct reproductive costs in female spotted hyenas, but is a prerequisite for male mating. Proc. Biol. Sci. 269:1981-1987, 2002.

East, M.L., Moestl, K., Benetka, V., Pitra, C., Honer, O.P., Wachter, B. and Hofer, H.: Coronavirus infection of spotted hyenas in the Serengeti. Vet. Microbiol. 102:1-9, 2004.

Enders, A.C., Blankenship, T.N., Conley, A.J. and Jones, C.J.P.: Structure of the midterm placenta of the spotted hyena, Crocuta crocuta , with emphasis on the diverse hemophagous regions. Cells Tissues Organs 183:141-155, 2006.

Glickman, S.E., Coscia, E.M., Frank, L.G., Licht, P., Weldele, M.L. and Drea, C.M.: Androgens and masculinization of genitalia in the spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta). 3. Effects of juvenile gonadectomy. J. Reprod. Fertil. 113:129-135, 1998.

Glickman, S.E., Cunha, G.R., Drea, C.M., Conley, A.J. and Place, N.J.: Mammalian sexual differentiation: lessons from the spotted hyena. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 17:349-356, 2006.

Gotch, A.F.: Mammals – Their Latin Names Explained. Blandford Press, Poole , Dorset , 1979.

Gregory, W.K. and Hellman, M.: On the evolution and major classification of the civets (Viverridae) and allied fossil and recent Carnivora : a phylogenetic study of the skull and dentition. Proc. Amer. Phil. Soc. 81:309-392, 1939.

Griner, L.A. : Pathology of Zoo Animals. Zoological Society of San Diego , San Diego , California , 1983.

Holekamp, K.E., Boydston, E.E., Szykman, M., Graham, I.I., Nutt, K.J., Birch, S., Piskiel, A. and Singh, M.: Vocal recognition in the spotted hyaena and its possible implications regarding the evolution of intelligence. Anim. Behav. 58:383-395, 1999.

Honer, O.P., Wachter, B., Speck, S., Wibbelt, G., Ludwig, A., Fyumagwa, R.D., Wohlsein, P., Lieckfeldt, D., Hofer, H. and East, M.L.: Severe Streptococcus infection in spotted hyenas in the Ngorongoro Crater, Tanzania . Vet. Microbiol. 115:223-228, 2006.

Hsu, T.C. and Benirschke, K.: An Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes. Vol. 2, Folio 78, 1968.

Koepfli, K.P., Jenks, S.M., Eizirik, E., Zahirpour, T., Van Valkenburgh, B. and Wayne , R.K.: Molecular systematics of the Hyaenidae: relationships of a relictual lineage resolved by a molecular supermatrix. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 38:603-620, 2006.

Künkel, R.: Die Dominas der Nacht. Natur & Kosmos. July, pp.92-101, 2002.

Licht, P., Frank, L.G., Pavgi, S., Yalcinkaya, T.M., Siiteri, P.K. and Glickman, S.E.: Hormonal correlates of ‘masculinization' in female spotted hyaenas (Crocuta crocuta). 2. Maternal and fetal steroids. J. Reprod. Fertil. 95:463-474, 1992.

Licht, P., Hayes, T., Tsai, P., Cunha, G., Kim, H., Golbus, M., Hayward , S., Martin, M.C., Jaffe, R.B. and Glickman, S.E.: Androgens and masculinization of genitalia in the spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta). 1. Urogenital morphology and placental androgen production during fetal life. J. Reprod. Fertil. 113:105-116, 1998.

Matthews, L.H.: Reproduction in the spotted hyaena, Crocuta crocuta (Erxleben). Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London , Series B. 230:1-78, 1939.

Morton, W.R.: Placentation in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben). J. Anat. 91:374-382, 1957.

Mossman, H.W. and Duke, K.L.: Comparative Morphology of the Mammalian Ovary. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison , Wisconsin , 1973.

Neaves, W.B., Griffin , J.E. and Wilson, J.D.: Sexual dimorphism of the phallus in spotted hyaena (Crocuta crocuta). J. Reprod. Fertil. 59:509-513, 1980.

Nobel, T.A., Klopfer, U., Perl, S. and Yakobson, B.: Lymphosarcoma in a spotted hyena, Crocuta crocuta . J. South Afr. Vet. Assoc. 54:209, 1983.

Nowak, R.M.: Walker 's Mammals of the World. 6 th ed. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1999.

O'Brien, S.J., Menninger, J.C. and Nash, W.G., eds.: Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes. Wiley-Liss; A. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken , N.J. , 2006.

Oduor-Okelo, D. and Neaves, W.B.: The chorioallantoic placenta of the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben). Anat. Rec. 204:215-222, 1982.

Perelman, P.L., Graphodatsky, A.S., Serdukova, N.A., Nie, W., Alkalaeva, E.Z., Fu, B., Robinson, T.J. and Yang, F.: Cytogenet. Genome Res. 108:348-354, 2005.Place, N.J., Weldele, M.L. and Wahaj , S.A. : Ultrasonic measurements of second and third trimester fetuses to predict gestational age and date of parturition in captive and wild spotted hyenas Crocuta crocuta . Theriogenology 58:1047-1055, 2002.

Schwerin , M. and Pitra, C.: Sex determination in spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta) by restriction fragment length polymorphism of amplified ZFX/ZFY loci. Theriogenology 41:553-559, 1994.

Vassetzky , N.S. and Kramerov, D.A.: CAN – a pan-carnivore SINE family. Mamm. Genome 13:50-57, 2002.

Weigl, R.: Longevity of Mammals in Captivity; From the Living Collections of the World. [Kleine Senckenberg-Reihe 48]. E. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Nägele und Obermiller), Stuttgart, 2005.

Wurster, D.H. and Gray, C.: The chromosomes of the spotted hyaena. Mammal. Chrom. Newsl. 8:197, 1967.

Wurster, D.H. and Benirschke, K.: Comparative cytogenetic studies in the Order Carnivora. Chromosoma 24:336-382, 1968.

Wurster, D.H., Benirschke, K. and Gray, C.W.: Determination of sex in the spotted hyaena. Intern. Zoo Yearb. 10:143-144, 1970.

Wurster-Hill, D.H. and Centerwall, W.R.: The interrelationships of chromosome banding patterns in canids, mustelids, hyena and felids. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 34:178-192, 1982.

Wynn, R.M. and Amoroso, E.C.: Placentation in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta Erxleben), with particular reference to the circulation. Amer. J. Anat. 115:327-362, 1964.

Wynn, R.M., Hoschner, J.A. and Oduor-Okelo, D.: The interhemal membrane of the spotted hyena: an immunohistochemical reappraisal. Placenta 11:215-221, 1990.