| |

13)

Genetics

Personal communications from Dr. W. Jorge in Brazil indicates that all five

specimens studied by him had 54 chromosomes, with an XX/XY sex determining

mechanism. The same author, however, provided additional details in his

later contribution (Jorge et al., 1985). B. tridactylus had 52 elements,

B. infuscatus (probably variegatus) had 54 chromosomes, and a specimen

of B. variegatus had 55 chromosomes. In a later contribution, Jorge

& Pinder (1990) studied the very much endangered Bradypus torquatus

from Northern Brazil and found them to have 2n=50, with XX/XY sex determining

mechanism.

No hybrids have been described.

14)

Immunology

I know of no immunological studies done in sloths.

15)

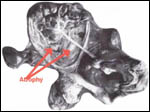

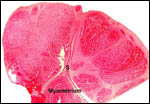

Pathological features

Diniz and Oliveira (1999) described the clinical and pathological conditions

of sloths in captivity. They found digestive and respiratory problems

to be the most notable. A variety of parasites were found in fecal examinations

and they stated that the first 6 months in captivity were the most critical.

Thereafter, management is less problematic. Seymour et al. (1983) isolated

a large number of poorly studied viruses from sloths in Panama. Further

details on parasites infecting the sloths may be found in contributions

to the monograph by Montgomery (1985).

16)

Physiologic data

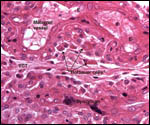

A variety of physiologic studies have been undertaken in Bradypus.

For instance, da Mota et al. (1992) have studied pancreatic endocrine

cells and found that glucagon-producing cells are much commoner than found

in the pancreas of human or laboratory animals. They related this to their

folivorous diet and possibly to their phylogeny. A comprehensive review

of sloths' physiology is found in the contribution by Gilmore et al. (2000).

In their additional paper of 2001, these authors specifically elaborated

on the hair structure of sloths with its algal growth, as well as their

ecology of carrying specific disease agents (viruses, parasites, and leishmania).

The cardiovascular adaptation to postural change was studied by Duarte

et al. (1982). Many other fascinating details of their physiology are

highlighted in an editorial (1974), such as the abdominal testes, the

conservation of temperature, the infrequent urination and defecation.

17)

Other resources

Some cell strains are available from CRES

at the San Diego Zoo by contacting Dr. Oliver Ryder at: oryder@ucsd.edu.

18)

Other remarks - What additional Information is needed?

Endocrine studies of placentas and gestation are needed to identify the

possible presence or the absence of placental gonadotropins. The presence

of so large a fetal adrenal gland demands the study of fetal endocrine

aspects.

Acknowledgement

I appreciate very much the help of the pathologists at the San Diego Zoo.

References

Becher, H.: Zur Kenntnis der Placenta vom Bradypus tridactylus.

Z. Anat. Entwicklungsgesch. 61:114-136, 1921.

Benirschke,

K. and Powell, H.C.: On the placentation of sloths. Pp. 237-241, In, Montgomery,

G.G., ed.: The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas.

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 1985.

Delsuc,

F., Catzeflis, F.M., Stanhope, M.J. and Douzery, E.J.: The evolution of

armadillos, anteaters and sloths depicted by nuclear and mitochondrial

phylogenies: implications for the status of the enigmatic fossil Eurotamandua.

Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B Biol. 268:1605-1615, 2001.

Diniz,

L.S. and Oliveira, P.M.: Clinical problems of sloths (Bradypus sp.

and Choloepus sp.) in captivity. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 30:76-80, 1999.

Duarte,

D.P., da Costa, C.P. and Huggins, S.E.: The effects of posture on blood

pressure and heart rate in the three-toed sloth, Bradypus tridactylus.

Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 73:697-702, 1982.

Editorial:

Sloth's compensations. The Lancet ii:1054, 1974.

Gilmore,

D.P., da-Costa, C.P. and Duarte, D.P.: An update on the physiology of

two- and three-toed sloths. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 33:129-146, 2000.

Gilmore,

D.P., da Costa, C.P. and Duarte, D.P.: Sloth biology: an update on their

physiological ecology, behavior and role as vectors of arthropods and

arboviruses. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 34:9-25, 2001.

Greenwood,

A.D., Castresana, J., Feldmaier-Fuchs, G. and Paabö, S.: A molecular

phylogeny of two extinct sloths. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 18:94-103, 2001.

Heuser,

C.H. and Wislocki, G.B.: Early development of the sloth (Bradypus griseus)

and its similarity to that of man. Contrib. Embryol. Carnegie Inst. Washington

25:1-13, 1935.

Hoke,

J.: Oh, it's so nice to have a sloth around the house. Smithsonian 18:88-98,

1987.

Jorge,

W., Orsi-Souza, A.T. and Best, R.: The somatic chromosomes of Xenarthra.

Pp.121 in, The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas.

G.G. Montgomery, ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 1985.

Jorge,

W. and Pinder, L.: Chromosome study on the maned sloth Bradypus torquatus

(Bradypodidae, Xenarthra). Cytobios 62:21-25, 1990.

King,

B.F., Pinheiro, P.B.N. and Hunter, R.L.: The fine structure of the placental

labyrinth in the sloth, Bradypus tridactylus. Anat. Rec. 202:15-22,

1982.

Lange,

D.de: Quelques remarques sur la placentation de "Bradypus".

Compt. Rend. Assoc. Anat. Liège 21:321-333, 1926.

Meritt,

D.A. and Meritt, G.F.: Sex ratios of Hoffmann's sloth, Choloepus hoffmanni

Peters, and three-toed sloth, Bradypus infuscatus Wagler, in Panama.

Amer. Midl. Nat. 96:472-473, 1976.

Montgomery,

G.G., ed.: The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas.

Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 1985.

Moser,

H.G. and Benirschke, K.: The fetal zone of the adrenal gland in the nine-banded

armadillo, Dasypus novemcinctus. Anat. Rec. 143:47-60, 1962.

Da

Mota, D.L., Yamada, J., Gerge, L.L. and Pinheiro, P.B.: An immunohistochemical

study on the pancreatic endocrine cells of the three-toed sloth, Bradypus

variegates. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 55:203-209, 1992.

Nowak,

R.M.: Walker's Mammals of the World. 6th ed. The Johns Hopkins Press,

Baltimore, 1999.

Seymour,

C., Peralta, P.H. and Montgomery, G.G.: Viruses isolated from Panamanian

sloths. Amer. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 32:1435-1444, 1983.

Wetzel,

R.M. and Avila-Pires, D.D. de: Identification and distribution of the

recent sloths of Brazil (Edentata). Rev. Bras. Biol. 40:831-836, 1980.

Wetzel,

R.M. and Kock, D.: The identity of Bradypus variegatus Schinz (Mammalia,

Edentata) Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 86:25-34, 1973.

Wetzel,

R.M.: Systematics, distribution, ecology, and conservation of South American

edentates. Pp. 345-375, in "Mammalian Biology in South America. Special

Publication Series of the Pymatuning Laboratory of Ecology, University

of Pittsburg, Vol. 6, 1982.

Wetzel,

R.M.: The identification and distribution of recent Xenarthra (=Edentata).

Pp. 5-21, In, Montgomery, G.G., ed.: The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos,

Sloths, and Vermilinguas. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, 1985.

Wislocki,

G.B.: On the placentation of the sloth (Bradypus griseus). Contrib.

Embryol. Carnegie Inst. Washington 16:7-19, 1925.

Wislocki,

G.B.: Further observations upon the placentation of the sloth (Bradypus

griseus). Anat. Rec. 32:45-51, 1926.

Wislocki,

G.B.: On the placentation of the tridactyl sloth (Bradypus griseus)

with a description of some characters of the fetus. Contrib. Embryol.

Carnegie Inst. Washington 19:211-228, 1927.

Wislocki,

G.B.: Further observations upon the minute structure of the labyrinth

in the placenta of the sloths. Anat. Rec. 40:385-395, 1928.

|