| (Clicking

on the thumbnail images will launch a new window and a larger version

of the thumbnail.) |

| Last updated: Oct 2, 2007. |

Scimitar (-horned) Oryx

Oryx dammah (tao)

Dalen Agnew & Kurt Benirschke

Order: Artiodactyla

Family: Bovidae (Hippotragini)

1) General Zoological Data

The anatomical characteristics have been described in detail by Dolan (1966) who also provided data on the captive collections existing at that time. He referred to Simpson (1945) as the principal author to describe the classification of this species. Their maximum survival has been 27 years, according to Weigl (2005). Gotch (1979) derives oryx from the Greek orux=gazelle, antelope, and scimitar from its saber-shaped horn, and dammah from damma=the Latin for fallow deer.

These animals are semi-desert species of northern Africa and are severely endangered (Wilson & Reeder, 1992); indeed, some web sites indicate that the animal may be extinct in the wild and is kept only in some reserves and zoological gardens (see also Dolan, 1966). On the other hand, of the many animals that are kept in Zoological Gardens, Nowak (1999) stated that this is the second most commonly exhibited antelope in captivity, with 500 specimens in US Zoos alone. In their review of infant mortality of inbred ungulates, Ralls et al. (1979) showed a significant increase of infant deaths over non-inbred neonates.

|

Scimitar-horned oryx at San Diego Zoo’s Wild Animal Park. |

2) General Gestational Data

Mentis (1972) gives the length of gestation as being 9-10 month; Dolan (1966) stated 270-300 days; but Hayssen et al. (1993) give the length of gestation as around 242 days. There is only one neonate, twins have not been recorded. The male term newborn of this gestation weighed 8,160 g; the average weight is 9,300 g (Ferrell et al., 2001).

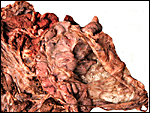

This placenta weighed 875 g and was retrieved at the Potter Zoo Park (Lansing, Michigan). There were 88 cotyledons with some of them being quite small (<0.5 cm). Most were 3-5 cm in width. Adult animals weigh around 180+ kg; and this dam was 8 years old.

3) Implantation

Early stages of implantation have not been described and they are badly needed.

4) General Characterization of the Placenta

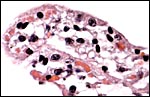

This is a multicotyledonary epitheliochorial placenta that is generally quite similar to that of many other Bovidae.

5) Details of fetal/maternal barrier

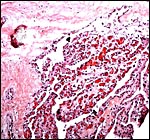

The trophoblast is in direct contact with the uterine epithelium (not shown) and occasional large-nucleated binucleate cells are present, as is also common in Bovidae. At the margins of this placenta the tissue was a rusty brown color and probably represents the hemophagous zone of ruminants.

|

Chorionic portion (above) of congested cotyledon. |

|

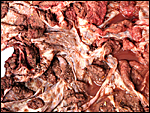

Villous surface with indentation of trophoblast by fetal capillaries. |

|

Surface of one villus with binucleate trophoblast. |

6) Umbilical cord

The umbilical cord measured at least 15 cm, had four blood vessels and an allantoic duct. The duct was lined by a complex layer of transitional urothelium. The umbilical cord’s surface has extensive regions (caruncles) of squamous metaplasia. Spirals were not observed to have been present. In addition to the major four fetal blood vessels in the umbilical cord, numerous small vessels of varying diameter were found. Some of these (few) accompanied the allantoic duct. These smaller vessels are often referred to as vasa vasorum.

|

Allantoic duct in umbilical cord at left. Large fetal artery at right. |

|

Allantoic duct (urachus) in umbilical cord. |

7) Uteroplacental circulation

This has not yet been studied.

8) Extraplacental membranes

A large allantoic sac was lined by flattened epithelium and its connective tissue has numerous blood vessels. The amnionic sac is also large, lacks blood vessels, and it is lined by flat squamous epithelium. Hippomanes were not encountered.

|

Amnion and allantoic membranes between cotyledons. |

9) Trophoblast external to barrier

In analogy to other Bovidae, no uterine invasion occurs and there is no extravillous trophoblast.

10) Endometrium

I have not had access to the endometrium during gestation.

11) Various features

None are known to me.

12) Endocrinology

The ovarian function and cycle have been studied by several investigators. Thus, Shaw et al. (1995) monitored ovarian function with the determination of 20̉α-progestagen metabolites in fecal samples. Morrow & Monfort (1998) used sonography, RIA of serum estradiol, progesterone, and LH as well as fecal estrogen and progestin analysis to determine the ovarian activity. They correlated these results with sonographic ovarian follicular features and the appearance of the corpus luteum. They also determined that the corpus luteum was 32 mm in size.

13) Genetics

Claro et al. (1994) determined that scimitar-horned oryx have 58 chromosomes in their study of 5.1 animals and employing C-, G- and R-banding techniques. On the other had, the scimitar-horned oryx examined at San Diego Zoo had between 56 and 58 chromosomes (as shown by O’Brien & Menninger, (2006). The ‘fusion chromosome’ that is responsible for the differences and that is shown so nicely in the following picture was studied in some detail by Kumamoto et al. (1999). All hippotragine species had a fixed 1:25 fusion chromosome, but different elements were fused in different species, indicating that a Robertsonian mechanism may have played a significant role in their speciation. It is thus all the more surprising that the hybrid between an Arabian oryx and a scimitar oryx proved to be fertile. On the other hand, it is unknown what the karyotypes of the parents were and they may not have had a fusion element. Gray (1972) listed only one hybrid with an Arabian oryx that was fertile.

Because of the possible extinction of this species in the wild, the genetic structure has become of additional interest. Thus, Iyengar et al. (2007) studied microsatellites and mitochondrial control regions of several European and some other captive herds. They were surprised to find a considerable divergence of mitochondrial haplotypes and related this to climate data from their points of origin during the past.

|

Karyotype as shown by O’Brien et al. (2006) with a 2;15 translocation. |

14) Immunology

I have not been able to find any references.

15) Pathological features

Flach et al. (2002) identified gamma herpesvirus DNA in scimitar-horned oryx as well as in many other bovid species. This virus caused cytopathogenicity in kidney cultures and malignant catarrhal fever in a rabbit. Griner (1983) examined a large number of these animals at San Diego Zoo at necropsy. Neonatal mortality was an important cause of death in his work, with omphalitis being of some importance. Otherwise, infectious causes of death were rare and no systemic diseases, malignancies or congenital anomalies were observed. Chai (1999), on the other hand, reported the occurrence of bacterial endocarditis due to Streptococcus uberis in a captive animal that led to death. Oocysts of Eimeria oryxae sp. were detected in the feces of captive animals in a zoo of Saudi Arabia (Alyousif & Al-Shawa, 2002). Goossens et al. (2005) conducted an extensive survey of fecal helminths in Belgian zoos and found 36% of the animals to be infected, most without symptomatology. A listerial organism was identified in numerous animals and in the grassy enclosure by Bauwens et al. (2001) in Planckendael (Belgium) but they caused no problems. Kirkwood & Cunningham (1994) reported on several Bovidae with scrapie, including one scimitar-horned oryx from Britain. Frölich & Flach (1998) surveyed 37 Oryx dammah at Whipsnade for several viral infection-induced antibodies and identified many to have such antibodies.

16) Physiologic data

Basic hematological data were supplied in the article by Pospisil et al. (1984). Much more detail of the neonatal weight, blood values, pulse rate, temperature and many blood values was made available by Ferrell et al. (2001) who studied these parameters in Sable antelope, Addax, Scimitar-horned oryx and Arabian oryx. Hagey at al. (1997) showed that the bile acid composition changes from neonatal ages to adult stages through the incorporation of dietary elements. The effects of immobilizing drugs was studied by Pearce & Kock (1989). They cautioned that xylazine is essential for complete sedation and that early intubation is needed to prevent regurgitation and aspiration.

Roth et al. (1998, 1999) provided a very detailed protocol for the obtaining, freezing, thawing and in-vitro-fertilizationof bovine ova. Their success rate was high and, amazingly, oocytes penetration and even embryo formation was possible with such oryx semen. They also referred to the initial production of a live offspring of this endangered species by these means. In a subsequent study (Morrow et al., 2000), they synchronized ovulation with a prostaglandin protocol and followed the semen collection protocol of the past; they thus produced three live offspring after 247 days gestation and one after 249 days. Kouba et al. (2001) followed similar protocols and used additionally fringe-eared oryx semen. While the experiment worked with scimitar-horned oryx semen, the fringe-eared experiment failed. Thus, differences appear to exist and these were unanticipated.

17) Other resources

Numerous cell lines from animals at San Diego Zoo are available by contacting Dr. O. Ryder at oryder@ucsd.edu.

18) Other remarks – What additional Information is needed?

Early stages of placentation have not been studied.

Acknowledgement

The animal photograph in this chapter comes from the Zoological Society of San Diego. The placenta was kindly made available by Dr. Tara Harrison of the Potter Park Zoo.

References

Alyousif, M.S. and Al-Shawa, Y.R.: A new coccidian parasite (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from the scimitar-horned oryx, Oryx dammah. J. Egyp. Soc. Parasitol. 32:241-246, 2002.

Bauwens, L., Vercammen, F. and de Meurichy, W.: Occurrence of Listeria spp. In captive antelope herds and their environment. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 32:514-518, 2001.

Chai, N.: Vegetative endocarditis in a scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 30:587-588, 1999.

Claro, F., Hayes, H. and Cribiu, E.P.: The C-, G-, and R-banded karyotypes of the Scimitar-horned Oryx (Oryx dammah). Hereditas 120:1-6, 1994.

Dolan, J.M.: Notes on the scimitar-horned oryx Oryx dammah (Cretzschmar 1826). Intern. Zoo Yearbook 6:219-229, 1966.

Ferrell, S.T., Radcliffe, R.W., Marsh, R., Thurman, C.B., Cartwright, C.M., de Maar, T.W.J., Blumer, E.S., Spevak, E. and Osofsky, S.A.: Comparisons among selected neonatal biomedical parameters of four species of semi-free ranging Hippotragini: Addax (Addax nasomaculatus), Scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah), Arabian oryx (Oryx leucoryx), and Sable antelope (Hippotragus niger). Zoo Biol. 20:47-54, 2001.

Flach, E.J., Reid, H., Pow, I. and Klemt, A.: Gamma herpesvirus carrier status of captive artiodactyls. Res. Vet. Sci. 73:93-99, 2002.

Frölich, K. and Flach, E.J.: Long-term viral serology of semi-free-living and captive ungulates. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 29:165-170, 1998.

Goossens, E., Dorny, P., Boomker, J., Vercammen, F. and Vercruysse, J.: A 12-month survey of the gastro-intestinal helminthes of antelopes, gazelles and giraffids kept at two zoos in Belgium. Vet. Parasitol. 127:303-312, 2005.

Gotch, A.F.: Mammals – Their Latin Names Explained. Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset, 1979.

Gray, A.P.: Mammalian Hybrids. A Check-list with Bibliography. 2nd edition.

Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux Farnham Royal, Slough, England, 1972.

Griner, L.A.: Pathology of Zoo Animals. Zoological Society of San Diego, San Diego, California, 1983.

Hagey, L.R., Gavrilkina, M.A. and Hofmann, A.F.: Age-related changes in the biliary bile acid composition of bovids. Can. J. Zool. 75:1193-11201, 1997.

Hayssen, V., van Tienhoven, A. and van Tienhoven, A.: Asdell’s Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: a Compendium of Species-specific Data. Comstock/Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1993.

Iyengar, A., Gilbert, T., Woodfine, T., Knowles, J.M., Diniz, F.M., Brenneman, R.A., Louis, E.E. and Maclean, N.: Remnants of ancient genetic diversity preserved within captive groups of scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah). Mol. Evol. 16:2436-2449, 2007.

Kirkwood, J.K and Cunningham, A.A.: Epidemiological observations on spongiform encephalopathies in captive wild animals in the British Isles. Vet. Rec. 135:296-303, 1994.

Kouba, A.J., Atkinson, M.W., Gandolf, A.R. and Roth, T.L.: Species-specific sperm-egg interaction affects the utility of a heterologous bovine in vitro fertilization system for evaluating antelope sperm. Biol. Reprod. 65:1246-1251, 2001.

Kumamoto, A.T., Charter, S.J., Kingswood, S.C., Ryder, O.A. and Gallagher, D.S. Jr.: Centric fusion differences among Oryx dammah, O. gazella, and O. leucoryx (Artiodactyla, Bovidae). Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 86:74-80, 1999.

Mentis, M.T.: A review of some life history features of the large herbivores of Africa. The Lammergeyer16:1-89, 1972.

Morrow, C.J. and Monfort, S.L.: Ovarian activity in the scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah) determined by faecal steroid analysis. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 53:191-207, 1998.

Morrow, C.J., Wolfe, B.A., Roth, T.L., Wildt, D.E., Bush, M., Blumer, E.S., Atkinson, M.W. and Monfort, S.L.: Comparing ovulation synchronization protocols for artificial insemination in the scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 59:71-86, 2000.

Nowak, R.M.: Walker’s Mammals of the World. 6th ed. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1999.

O’Brien, S.J., Menninger, J.C. and Nash, W.G., eds.: Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes. Wiley-Liss; A. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, N.J., 2006.

Pearce, P.C. and Kock, R.A.: Physiological effects of etorphine, acepromazine and xylazine in the scimitar horned oryx (Oryx dammah). Res. Vet. Sci. 47:78-83, 1989.

Pospisil, J., Kase, F., Vahala, J. and Mouchova, I.: Basic hematological values in antelopes – II. The Hippotraginae and the Tragelaphinae. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 78:799-807, 1984.

Ralls, K., Brugger, K. and Ballou, J.: Inbreeding and juvenile mortality in small populations of ungulates. Science 206:1101-1102, 1979.

Roth, T.L., Weiss, R.B., Buff, J.L., Bush, L.M., Wildt, D.E. and Bush, M.: Heterologous in vitro fertilization and sperm capacitation in an endangered African antelope, the scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah). Biol. Reprod. 58:475-482, 1998.

Roth, T.L., Bush, L.M., Wildt, D.E. and Weiss, R.B.: Scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah) spermatozoa are functionally competent in a heterologous bovine in vitro fertilization system after cryopreservation on dry ice, in a dry shipper, and over liquid nitrogen vapor. Biol. Reprod. 60:493-498, 1999.

Shaw, H.J., Green, D.I., Sainsbury, A.W. and Holt, W.V.: Monitoring ovarian function in scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah) by measurement of fecal 20α-progestagen metabolites. Zoo Biol. 14:239-250, 1995.

Simpson, G.G.: Principles of classification and classification of mammals. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 85:i-xvi + 1-350, 1945.

Weigl, R.: Longevity of Mammals in Captivity; From the Living Collections of the World. [Kleine Senckenberg-Reihe 48]. E. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Nägele und Obermiller), Stuttgart, 2005.

Wilson, D.E. and Reeder, D.A.M.: Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. 2nd ed. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, 1992.