| (Clicking

on the thumbnail images will launch a new window and a larger version

of the thumbnail.) |

| Last updated: March 4, 2007. |

Ondatra zibethicus

Order: Rodentia

Family: Muridae

1) General Zoological Data

Muskrats are represented by a single species; they have been referred to as “Fiber”, have numerous subspecific synonyms, and they are widely distributed through North America . In 1905 they have also been introduced into Czechoslovakia , into England , and into the larger European Continent, principally as a fur-bearing animal. The importance as a source of fur has continued to date. In Europe , however, they escaped from the fur trade breeding compounds and have subsequently formed large colonies with destructive consequences; especially vulnerable have been the dikes of Holland .

This river-loving species is an excellent diver, can swim long distances submerged and the animals hold their breath for many minutes. They are basically herbivorous, consume cattails and plants such as bulrush and the water lily; in these marshes muskrats build a dome-like home with access to the river. Their hair is very dense and water-repellant; the hind toes are partially webbed and have lateral hair. The laterally flattened tail is used as a rudder (Nowak, 1999). The longevity is listed as 5+ years (Weigl, 2005; but Nowak states that it may live as long as 10 years in captivity). Its name, muskrat, derives from the characteristic odor of some perianal glands. The name ‘ ondatra ' is said to be the Indian name of muskrat, and zibethicus presumably comes from the animal being civet-colored (Gotch, 1979). In Germany , to which the animal has also been exported and where it has caused much destruction, the animal is called ‘Bisamratte'. The males weigh around 923 g; females are 839 g on average. The mostly nocturnal animals are about 51 cm long and have a somewhat flattened, scaly tail that measures 24 cm. Thenius & Hofer (1960) relate the animal to other “Wühlmäuse” (Microtinae) and to the Floridian Neofiber , and they suggest it to have a lifestyle similar to that of beavers.

|

Muskrat, as illustrated by Tveten (Web site). |

2) General Gestational Data

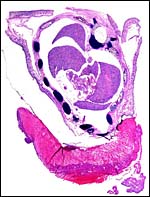

The pregnant female whose specimen is described here had two fetuses, each weighing 19.8 g with placenta; the placenta, separately weighed, was 2.8 gm. It measured 4 cm in greatest diameter and 1.5 cm in greatest thickness. The animal is polyestrous, has several litters a year and carries 1-11 young. The neonates weigh around 21 g and are naked, blind and helpless for some time. The gestation of muskrats lasts 22-30 days. Unfortunately, this pregnant female was frozen before it could be dissected and formalin-fixed; thus, the microscopic preservation of the placental structures is compromised.

|

Fetal muskrat near term with attached placenta. |

| Cross section of the fetus with attached placenta. | |

3) Implantation

No early stages of implantation have been described.

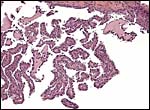

4) General Characterization of the Placenta

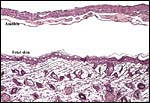

Implantation is superficial and interstitial, initially antimesometrial, with a single disk forming mesometrially; amniogenesis is by folding; there is a yolk sac placenta with very small allantois; the disk is labyrinthine in structure, the relation to the maternal system is deciduate and the fetal/maternal barrier is hemochorial (Ramsey, 1982).

|

Fetal surface of the placental disk. |

|

Cross section of the placental disk. |

|

Cross section of the fetal chest with attached disk-like placenta. |

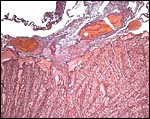

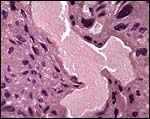

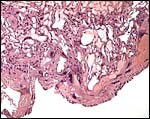

5) Details of fetal/maternal barrier

This placenta has a hemochorial relationship, much like that of other rodents. The initially present cytotrophoblast that was presumably present has now disappeared and the vascular spaces are lined by syncytium.

6) Umbilical cord

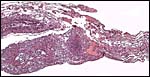

The extremely delicate umbilical cord was 1 cm long and had no twists. The two portions of cord (chorioallantoic and vitelline) each possess two vessels. The surface is a thin layer of amnion.

| The delicate, 1 cm-long umbilical cord connects the abdomen to the placental disk. | |

|

Section of umbilical cord. The chorioallantoic portion is below, that of the vitelline circulation is above. |

7) Uteroplacental circulation

No studies have been conducted but the utero-placental vasculature is likely to be similar to that of other rodents.

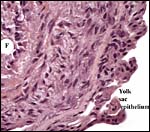

8) Extraplacental membranes

The amnion is extremely thin and avascular; there is only a transitory allantoic sac and no allantoic membrane is recognized in this term gestation. The vitelline epithelium is columnar, has a villous structure at the margin of the disk, and it is apposed to the decidua (the ‘yolk-sac splanchnopleure'). It is a vascular membrane.

9) Trophoblast external to barrier

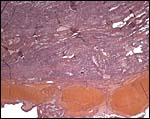

Mossman (1987) depicted the trophoblastic giant cells in the marginal region of this ‘cricetid rodent' that are shown below. He demonstrated their survival to term in muskrat and other rodents although Amoroso (1961) had suggested that their lifespan was quite short.

|

The base of the placental disk has some large maternal decidual vessels attached to the junctional zone. |

|

The giant trophoblastic cells in the floor as described by Mossman (1987). |

10) Endometrium

There is early decidualization but the amount found at term is trivial.

11) Various features

No subplacenta is formed.

12) Endocrinology

The ovary is described as being much the same as that of other muroid rodents (Mossman & Lukes, 1973), has a bursa, and has been studied in greater detail by Miegel (1953). Other endocrine substances have apparently not yet been studied.

13) Genetics

The chromosome number of 2n=54 has first been described by Makino (1953); Moore et al. (1966), and Kihlberg et al. (1969) studied the chromosomes more recently. All chromosomes are acrocentrics, except for one small metacentric element. Nadler (1969) referred to Matthey (1957) as having identified animals with 54 and 56 chromosomes. Hybrids have not been mentioned in the literature.

|

Karyotypes of female and male muskrats (from Moore et al., 1966). |

14) Immunology

No studies are known to me and none can be found in the literature.

15) Pathological features

A variety of infectious diseases are known to have affected muskrats. Thus, Tyzzer's disease, formerly known as Errington's disease has been reported from Iowa (www.michigan.gov/dnr/ ; also Wobeser et al., 1979) and from many other US States; it is due to the infection with Clostridium piliforme . Giardiasis was reported by Erlandsen et al. (1990), a variety of other infections (Lyme borreliosis, hemorrhagic fever, lymphocytic choriomeningitis, tick-borne encephalitis, Q-fever and Weil's leptospirosis were referred to by Moll van Charante et al. (1998); adenoviral infections in Illinois were reported by Wenn & Woods (2001), and finally, tularemia was identified and is mentioned in the web site: www.wildlifedamage.com/muskrats.htm.

16) Physiologic data

I am not aware of any relevant studies.

17) Other resources

Apparently no cell strains exist CRES does not have any cultures.

18) Other remarks – What additional Information is needed?

Better and modern cytogenetics, early implantational stages and a better-preserved placenta are needed.

Acknowledgement

The animal photograph in this chapter comes from the web site “The Mammals of Texas” (www.nsrl.ttu.edu).

References

Amoroso, E.C.: Placentation. Chapter 15, pp.127-311, In, Marshall 's Physiology of Reproduction, V.II, A.S. Parkes, ed. Second Edition. Little, Brown & Co. Boston , 1961.

Erlandsen, S.L., Sherlock, L.A. , Bemrick, W.J., Ghobrial, H. and Jakubowski, W.: Prevalence of Giardia spp. In beaver and muskrat populations in northeastern states and Minnesota : detection of intestinal trophozoites at necropsy provides greater sensitivity than detection of cysts in fecal samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:31-36, 1990.

Gotch, A.F.: Mammals – Their Latin Names Explained. Blandford Press, Poole , Dorset , 1979.

Kihlberg, C.G., Gustavsson, I. and Sundt, C.O.: The mitotic and meiotic chromosomes of the muskrat (Ondatra zibethica L.). Acta Vet. Scand.10:181-192, 1969.

Makino, S.: Science 118:630, 1953.

Matthey, R.: Cytologie comparée systématique et phylogenie des microtinae (Rodentia – Murida). Rev. Suisse Zool. 64:39, 1957.

Miegel, B.: Die Biologie und Morphologie der Fortpflanzung de Bisamratte, (Ondatra zibethica L.). Z. Mikrosk.-anat. Forsch. 58:531-598, 1953.

Moll van Charante, A.W., Groen, J., Mulder, P.G., Rijpkema, S.G. and Osterhaus, A.D.: Occupational risk of zoonotic infections in Dutch forestry workers and muskrat catchers. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 14:109-116, 1998.

Moore , W. Jr., Elder, R.L. and Gillespie, L.J.: The chromosomes of the muskrat. J. Hered. 57:104, 1966.

Mossman, H.W.: Vertebrate Fetal Membranes. MacMillan, Houndmills, 1987.

Mossman, H.W. and Duke, K.L.: Comparative Morphology of the Mammalian Ovary. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison , Wisconsin , 1973.

Nadler, C.F.: Chromosomal evolution in rodents. Pp. 277-309 in: Benirschke, K., ed.: Comparative Mammalian Cytogenetics. Springer-Verlag , NY , 1969.

Nowak, R.M.: Walker 's Mammals of the World. 6 th ed. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1999.

Ramsey, E.M.: The Placenta. Human and Animal. Praeger Publishers, N.Y. 1982

Webb, D.M. and Woods, L.W.: Microscopic evidence of adenoviral infection in a muskrat in Illinois . J. Wildl. Dis. 37:643-645, 2001.

Weigl, R.: Longevity of Mammals in Captivity; From the Living Collections of the World. [Kleine Senckenberg-Rei he 48]. E. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Nägele und Obermiller), Stuttgart, 2005.

Wobeser, G., Barnes, H.J. and Pierce, K.: Tyzzer's disease in muskrats: re-examination of specimens of hemorrhagic disease collected by Paul Errington. J. Wildl. Dis. 15:525-527, 1979.