| |

Spontaneous abortions occur but are perhaps not so common as seen in human

gestations. This is particularly so in breeding colonies of Primate Research

Centers. Wilson (1972) reviewed this topic extensively. Around 10-15% of

gestations that occurred in Primate Research Centers abort spontaneously

or end in premature delivery. Many more do so when the females were freshly

imported. Similarly, Hertig et al. (1971) reported that nearly one half

of newly imported pregnant animals had either abortions or premature deliveries.

Most were due to common infections and/or measles infection. In contrast

to human studies of abortions, a majority of which are due to trisomies

or other chromosomal errors, such investigations have apparently not been

done in rhesus monkey colonies.

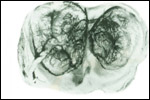

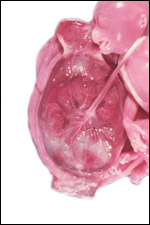

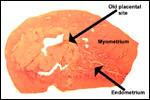

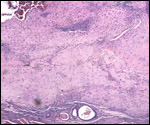

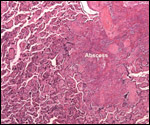

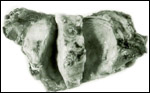

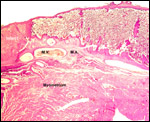

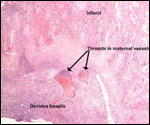

Placenta previa, abruptio placentae, infarcts and stillbirths with fetus

papyraceus all have been recorded in rhesus monkeys (Myers, 1972). Indeed,

Myers asserted that most of the anomalies or pathologic conditions seen

in human placentas may be observed in rhesus monkeys. Endometriosis, adenomyosis

and endometrial anomalies are some other pathologic features studied in

rhesus monkeys.

Structural abnormalities of neonatal primates have been studied by Wilson

(1972). A variety of congenital anomalies have been identified, but apparently

fewer than found in humans. Importantly, the same author clearly identified

the cause of phocomelia following a single dose of thalidomide. Several

of those animals are depicted in his report.

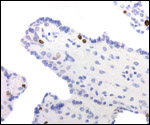

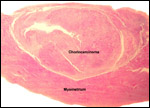

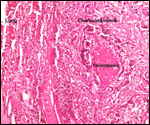

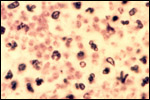

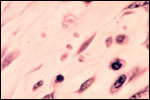

Several extrauterine choriocarcinomas have been reported, even in juvenile catarrhine monkeys. They may have arisen from germ cells or stem cells; alternatively they are associated with a teratoma. Their apparent relative frequency is nevertheless surprising and they can be quite destructive. The last-cited authors have used very modern tools for their exploration. (Farman et al. 2005; Giusti, et al. 2005; Marbaix et al., 2008; Moore et al., 2003; Toyosawa et al. 2000; Yamamoto et al. 2007).

16)

Physiologic data

Physiologic data on blood pressure and pulse rate of fetus and mother

in pregnant rhesus monkeys under anesthesia were reported by Misenhimer

& Ramsey (1970. In addition to that report, a wealth of information

has been accumulated in fetal and placental physiology of rhesus gestations.

Access to this literature can be achieved through the comprehensive book

of Ramsey and Donner (1980). Some information on the vasculature is summarized

above.

17)

Other resources

The Regional Primate Research Centers of the USA, several foreign research

centers, and industrial companies have large holdings of rhesus monkeys.

Most are now bred in captivity, very few are being imported. And the zoological

parks of the world, of course, house large numbers of these animals and

more commonly some of the related species. There is much expertise in

breeding and pathology in these agencies.

18)

Other remarks - What additional Information is needed?

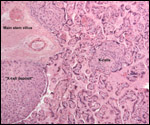

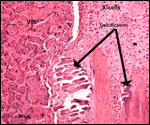

One of the more interesting future studies should be on the regulation

of the "X-cells", the extravillous trophoblast. Not only does

it achieve the implantation but also, it modifies the blood vessels of

the endometrium and produces a specific protein whose function is unknown

so far. The means by which MHC is modulated so as to prevent rejection,

the exploration of syncytin and syncytium formation will be of interest.

Observations on intrauterine mobility and its effect on spiraling (not

described in rhesus) of the cord should be made. Do MZ twins occur and

how is their placenta structured.

Acknowledgement

Most of the animal photographs in these chapters come from the Zoological

Society of San Diego. I appreciate also very much the help of the pathologists

at the San Diego Zoo.

References

Arts, N.F.Th. and Lohman, A.H.M.: An injection=corrosion study of the

fetal and maternal vascular systems in the placenta of the rhesus monkey.

Europ. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 4:133-141, 1974.

Atkinson,

L.E., Hotchkiss, J., Fritz, G.R., Surve, A.H., Neill, J.D. and Knobil,

E.: Circulating levels of steroids and chorionic gonadotropin during pregnancy

in the rhesus monkey, with special attention to the rescue of the corpus

luteum in early pregnancy. Biol. Reprod. 12:335-345, 1975.

Bartelmez,

G.W.: Cyclic changes in the endometrium of the rhesus monkey (Macaca

mulatta). Contrib. Embryol. Carnegie Institution # 227. 34:101-144,

1951.

Beck, A.J. and Beck, F.: The origin of intra-arterial cells in the pregnant

uterus of the macaque (Macaca mulatta). Anat. Rec. 158:111-114,

1967.

Benirschke,

K. and Kaufmann, P.: The Pathology of the Human Placenta. 4th ed. Springer-Verlag,

NY, 2000.

Boyson,

J.E., Iwanaga, K.K., Golos, T.G. and Watkins, D.I.: Identification of

a novel MHC class I gene, Mamu-AG, expressed in the placenta of a primate

with an inactivated G locus. J. Immunol. 159:3311-3321, 1997.

Bronson,

R., Volk, T.L. and Ruebner, B.H.: Involution of placental site and corpus

luteum in the monkey. Amer. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 113:70-75, 1972.

Bunton,

T.E.: Incidental lesions in nonhuman primate placentae. Vet. Pathol. 23:431-438,

1986.

Chez,

R.A., Schlesselman, J.J., Salazar, H. and Fox, R.: Single placentas in

the Rhesus Monkey. J. med. Primatol. 1:230-240, 1972.

Enders,

A.C. and King, B.F.: Formation and differentiation of extraembryonic mesoderm

in the rhesus monkey. Amer. J. Anat. 181:327-340, 1988.

Enders,

A.C. and Schlafke, S.: Differentiation of the blastocyst of the rhesus

monkey. Amer. J. Anat. 162:1-21, 1981.

Enders,

A.C., Hendrickx, A.G. and Binkerd, P.E.: Abnormal development of blastocysts

and blastomeres in the rhesus monkey. Biol. Reprod. 26:353-366, 1982.

Fa,

J.E.: The genus Macaca: a review of taxonomy and evolution. Mamm.

Rev. 19:45-81, 1989.

Farman, , C.A.: Benirschke, K., Horner, M. and Lappin, P: Ovarian choriocarcinoma in a rhesus monkey associated with elevated serum chorionic gonadotropin levels. Vet. Pathol. 42:226-229, 2005.

Fitch, H., Coen, R., Lindburg, D., Robinson, P., Hajek, P. Hesselink, J. and Crutchfield, S.: Cerebral palsy in a macaque monkey. Amer. J. Primatol. 14:181-187, 1988.

Galton,

M.: DNA content of placental nuclei. J. Cell. Biol. 13:183-191, 1962.

Geissmann,

T.: Twinning frequency in catarrhine primates. Human Evolution 5:387-396,

1990.

Giusti, A.M.F., Terron, A., Belluco, S., Scanziani, E. and Carccangiu, M.L.: Ovarian epithelioid trophoblastic tumor in a cynomolgus monkey. Vet. Pathol. 42:223-226, 2005.

Gray,

A.P.: Mammalian Hybrids. A Check-list with Bibliography. 2nd edition.

Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux Farnham Royal, Slough, England, 1972.

Gruenwald,

P.: Lobular structure of hemochorial primate placentas, and its relation

to maternal vessels. Amer. J. Anat. 136:133-152, 1973.

Hendrickx,

A.G.: Embryology of the Baboon. University of Chicago Press, Chicago,

1971.

Hertig,

A.T., King, N.W. and MacKey, J.: Spontaneous abortion in wild-caught rhesus

monkeys, Macaca mulatta. Labor. Animal Sci. 21:510-519, 1971.

Heuser,

C.H. and Streeter, G.L.: Development of the macaque embryo. Contrib. Embryol.

Carnegie Institution # 181. 29:9-55, 1941.

Hobson,

B.M.: Production of gonadotropin, oestrogens and progesterone by the primate

placenta. Adv. Reprod. Physiol. 5:67-102, 1971.

Hodgen,

G.D., Dufau, M.L., Catt, K.J. and Tullner, W.W.: Estrogens, progesterone

and chorionic gonadotropin in pregnant rhesus monkeys. Endocrinology 91:896-900,

1972.

Houston,

M.L. and Hendrickx, A.G.: Observations on the vasculature of the baboon

placenta (Papio sp.) with special reference to the transverse communicating

artery. Folia primatol. 9:68-77, 1968.

King,

B.F.: Developmental changes in the fine structure of rhesus monkey amnion.

Amer. J. Anat. 157:285-307, 1980.

King,

B.J.: Developmental changes in the fine structure of the chorion leave

(smooth chorion) of the rhesus monkey placenta. Anat. Rec. 200:163-175,

1981.

Knapp,

L.A., Lehmann, E., Piekarczyk, M.S., Urvater, J.A. and Watkins, D.I.:

A high frequency of Mamu-A*01 in the rhesus macaque detected by polymerase

chain reaction with sequence-specific primers and direct sequencing. Tissue

Antigens 50:657-661, 1997.

Knapp,

L.A., Cadavid, L.F. and Watkins, D.I.: The MHC-E locus in the most ancient

and well-conserved of all known primate class I histocompatibility genes.

J. Immunol. 160:180-196, 1998.

Kuroda,

M.C., Schmitz, J.E., Barouch, D.H., Craiu, A., Allen, T.M., Sette, A.,

Watkins, D.I., Forman, M.A. and Letvin, N.L.: Analysis of gag-specific

cytotoxic T lymphocytes in SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys by cell staining

with tetrameric MHC Class I/peptide complex. J. Exp. Med. 187:1373-1381,

1998.

Landsteiner,

K. and Wiener, A.S.: An agglutinable factor in human blood recognized

by immune sera for rhesus blood. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 43:223-224,

1940.

Lewis,

J. and Hertz, R.: Effects of early embryectomy and hormonal therapy on

the fate of the placenta in pregnant rhesus monkeys. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol.

Med. 123:805-809. 1966.

Lindburg,

D.G.: The rhesus monkey in north India: an ecological and behavioral study.

Primate Behav. 2:1-106, 1971.

Lindburg,

D.G., ed.: The macaques: studies in ecology, behavior, and evolution.

Van Nostrand Reinhold, NY, 1980.

Lindsey,

J.R., Wharton, L.R., Woodruff, J.D. and Baker, H.J.: Intrauterine choriocarcinoma

in a rhesus monkey. Pathol. Vet, 6:378-384, 1969.

Luckett,

W.P.: The fine structure of the placental villi of the rhesus monkey (Macaca

mulatta). Anat. Rec. 167:141-164, 1970.

Maddox,

D.E., Kephart, G.M., Coulam, C.B., Butterfield, J.H., Benirschke, K. and

Gleich, G.J.: Localization of a molecule immunochemically similar to eosinophil

major basic protein in human placenta. J. Exp. Med.. 160:29-41, 1984.

Marbaix, E., Defrere, S., Ho Minh Duc, K., Lousse J.-C. and Dehoux, J.-P.: Non-gestational malignant placental site trophoblastic tumor of the ovary in a 4-year-old rhesus monkey. Vet. Pathol. 45:375-378, 2008.

Martin,

C.B., Ramsey, E.M. and Donner, M.W.: The fetal placental circulation in

rhesus monkeys demonstrated by radioangiography. Amer. J. Obstet. Gynecol.

95:943-947, 1966.

Migaki,

G., Benirschke, K., McKee, A.E. and Casey, H.W.: Trichomonal granuloma

of the pelvic cavity in a rhesus monkey. Vet. Path. 15:679?681, 1978.

Misenhimer,

H.R. and Ramsey, E.M.: The effect of anesthesia and surgery in pregnant

rhesus monkeys. Gynec. Invest. 1:105-114, 1970.

Moore, C.M., Hubbard, G.B., Leland, M.M., Dunn, B.G. and Best, R.G.: Spontaneous ovarian tumors in twelve baboons: a review of ovarian neoplasms in nonhuman primates. J. Med. Primatol. 32:48-56, 2003.

Myers,

R.E.: The gross pathology of the Rhesus Monkey placenta. J. Reprod. Med.

9:171-198, 1972.

Myers,

R.E.: The pathology of the rhesus monkey placenta. Pp. 221-260. In, Symposium

on the Use of Non-human Primates for Research on Problems of Human Reproduction.

Sukhumi, 1971. WHO Research & Training Centre on Human Reproduction,

Karolinska, Sweden, 1972.

Myers,

R.E.: Placental pathology. Chapter 85 in, Spontaneous Animal Models of

Human Diseases, Vol. 1, E.J. Andrews, B.C. Ward, and N.H. Altman eds.,

Academic Press, NY, 1979. pp. 208-209.

Naaktgeboren,

C. and Wagtendonk, A.M.v.: Wahre Knoten in der Nabelschnur nebst Bemerkungen

über Plazentophagie bei Menschenaffen. Z. Säugetierk. 31:376-382,

1966.

Nathanielsz,

P.W., Figueroa, J.P. and Honnebier, M.B.O.M.: In the rhesus monkey placental

retention after fetectomy at 121 to 130 days' gestation outlasts the normal

duration of pregnancy. Amer. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 166:1529-1535, 1992.

Novy,

M.J., Aubert, M.L., Kaplan, S.L. and Grumbach, M.M.: Regulation of placental

growth and chorionic somatomammotropin in the rhesus monkey: Effects of

protein deprivation, fetal anencephaly, and placental vessel ligation.

Amer. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 140:552-562, 1981.

Nowak,

R.M.: Walker's Mammals of the World. 6th ed. The Johns Hopkins Press,

Baltimore, 1999.

Panigel,

M.: Comparative anatomical, physiological and pharmacological aspects

of placental permeability and haemodynamics in the non-human primate placenta

and in the isolated perfused human placenta. In, The Foeto-Placental Unit.

Pp.279-295, Excerpta Medica Internat. Congress Series # 183, Milan 1968.

Pepe,

G.J. and Albrecht, E.D.: Actions of placental and fetal adrenal steroid

hormones in primate pregnancy. Endocrine Reviews 16:608-648, 1995.

Pierce,

G.B., Midgley, A.R. and Beals, T.F.: An ultrastructural study of differentiation

and maturation of trophoblast of the monkey. Laboratory Invest. 13:451-464,

1964.

Raio,

L., Ghezzi, F., DiNaro, M. Franchi, M., Balestreri, D., Durig, P. and

Schneider, H.: In-utero characterization of the blood flow in the Hyrtl

anastomosis. Placenta 22:597-601, 2001.

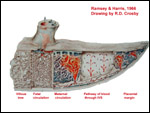

Ramsey,

E.M. and Harris, J.W.S.: Comparison of Uteroplacental vasculature and

circulation in the rhesus monkey and man. Contrib. To Embryol. # 261.

Carnegie Inst. Washington Publ. # 625. Vol. 38:59-70, 1966.

Ramsey,

E.M., Martin, C.B., McGaughey, H.S., Kaiser, I.H. and Donner, M.W.: Venous

drainage of the placenta in rhesus monkeys: Radiographic studies. Amer.

J. Obstet. Gynecol. 95:948-955, 1966.

Ramsey,

E.M.: Evaluation of Macaca mulatta as an experimental model for

studies of primate reproduction. In, Medical Primatology, part 1, pp.

308-316, 1972. Karger, Basel.

Ramsey,

E.M., Houston, M.L. and Harris, J.W.S.: Interactions of the trophoblast

and maternal tissues in three closely related primate species. Amer. J.

Obstet. Gynecol. 124-647-652, 1976.

Ramsey,

E.M., Chez, R.A. and Doppman, J.L.: Radioangiographic measurement of the

internal diameters of the Uteroplacental arteries in rhesus monkeys. Amer.

J. Obstet. Gynecol. 135:247-251, 1979.

Ramsey,

E.M. and Donner, M.W.: Placental Vasculature and Circulation. Anatomy,

Physiology, Radiology, Clinical Aspects. Atlas and Textbook. W.B. Saunders

Company, Philadelphia, 1980.

Richart,

R.: Studies of placental morphogenesis. I. Radioautographic studies of

human placenta utilizing tritiated thymidine. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med.

106:829-831, 1961.

Ruppenthal, G.C., Moore, C.M., Best, R.G., Walker-Gelatt, C.G., Delio, P.J. and Sackett, G.P.: Trisomy 16 in a pigtailed macaque (M. nemestrina) with multiple anomalies and developmental delays. Amer. J. Ment. Retard. 109:9-20, 2004.

Scott,

G.B.D.: Comparative Primate Pathology. Oxford University Press, 1992.

Socha,

W.W.: Blood groups of nonhuman primates. In, Comparative Biology. Vol.

1: Systematics, Evolution, and Anatomy. Pp. 299-333, A. R. Liss, 1986.

Spatz,

W.B.: Nabelschnur-Längen bei Insektivoren und Primaten. Z. Säugetierk.

33:226-239, 1968.

Starck,

D.: Vergleichende Anatomie und Evolution der Placenta. Verh. Anat. Gesellsch.

56th Versammlung, Zurich, 1959. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena, 1959. Pp.5-26.

Stock,

A.D. and Hsu, T.C.: Evolutionary conservatism in arrangement of genetic

material. A comparative analysis of chromosome banding between the rhesus

macaque (2=42, 84 arms) and the African green monkey (2n=60, 120 arms).

Chromosoma 43:211, 1973.

Torpin,

R.: Placentation in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Obstet.

Gynecol. 34:410-413, 1969.

Toyosawa, K., Okimoto, K., Koujitani, T. and Kikawa, E.: Choriocarcinoma and teratoma in the ovary of a cynomolgus monkey. Vet. Pathol. 37:186-188, 2000.

Wagenen,

G.v., Catchpole, H.R., Negri, J. and Butzko, D.: Growth of the fetus and

placenta of the monkey (Macaca mulatta). 23:23-34, 1965.

Wasmoen,

T.L., Benirschke, K. and Gleich, G.J.: Demonstration of immunoreactive

eosinophil granule protein major basic protein in the placenta and placentae

of non-human primates. Placenta 8:283-292, 1987.

Wasmoen,

T.L., McKean, D.J., Benirschke, K., Coulam, C.B. and Gleich, G.J.: Evidence

of eosinophil granule major basic protein in human placenta. J. Exp. Med.

170:2051-2063, 1989.

Weiss,

G., Weick, F., Knobil, E., Wolman, S.R. and Gorstein, F.: An X-O anomaly

and ovarian dysgenesis in a rhesus monkey. Folia primatol. 19:24, 1973.

Wiener,

A.S., Moor-Jankowski, J. and Gordon, E.B.: Blood groups of apes and monkeys.

V. Studies on the human blood group factors A,B,H and Le in old and new

world monkeys. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. 22:175-188, 1964.

Wilken,

J.A., Matsumoto, K., Laughlin, L.S., Lasley, B.L. and Bedows, E.: A comparison

of chorionic gonadotropin expression in human and macaque (Macaca fascicularis).

In press, 2001.

Wilson,

J. G.: Abnormalities of intrauterine development in non-human primates.

Pp. 261-292. In, Symposium on the Use of Non-human Primates for Research

on Problems of Human Reproduction. Sukhumi, 1971. WHO Research & Training

Centre on Human Reproduction, Karolinska, Sweden, 1972.

Wislocki,

G.B. and Streeter, G.L.: On the placentation of the macaque (Macaca

mulatta) from the time of implantation until the formation of the

definitive placenta. Contrib. Embryol. Carnegie Inst. 27:1-66, 1938.

Yamamoto, E., Ino, K. Yamamoto, T., Sumigama, S., Nawa, A., Nomura, S. and

Kikkawa, F: A pure nongestational choriocarcinoma of the ovary diagnosed with short tandem repeat analysis: case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 17:254-258, 2007.

|