| (Clicking

on the thumbnail images will launch a new window and a larger version

of the thumbnail.) |

| Last updated: June 9, 2006. |

Cercopithecus petaurista

Order: Primates

Family: Cercopithecidae

1) General Zoological Data

This species distributes in African forests from Guinea to Benin (Nowak, 1999; other authors refer to a distribution from Gambia to Ghana and, specifically, east of the Sassandra River) and the animals are characterized by their white nasal spot. They also possess large white cheeks, live in social groups of 20-30 animals and consume primarily fruit. Few detailed studies have been conducted on these animals in Africa and real details are mostly lacking from the sparse literature. The names derive from kerkos (Gr.) tail, pithekos (Gr.) ape; petauron (Gr.) perch or springboard and - ista (L.) denoting ability (Gotch, 1979). The longevity is 28 years according to Weigl (2005). This species characteristically produces singletons (Hayssen et al., 1993). A variety of Zoological Gardens display these animals.

|

Cercopithecus petaurista, the lesser spot-nosed monkey. |

2) General Gestational Data

The gestational length has been given as 165-170 days (others suggest 150-213 days), and the birth weight of 230 g was provided by Puschmann (2004). Males weigh up to 6 kg, females up to 4 kg. Twins have not been described as occurring and the species is not listed in the review by Geissmann (1990) on twinning in catarrhine monkeys.

3) Implantation

No reports of early implantational stages have been available to me. They are probably similar to those of rhesus monkeys and baboons but require new studies.

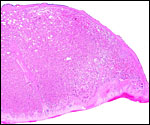

4) General Characterization of the Placenta

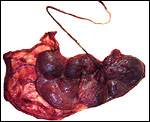

The placenta displayed here comes from a live birth at the San Diego Zoo in May of 2006. The placenta weighed 43 g, measured 13 x 5.5 x 1 cm and had a 20 cm long cord attached. It was composed of numerous somewhat separated cotyledons but did not assume the typical bilobed organ that is so often seen in this family. This is a villous, hemochorial placenta consisting of 6-8 fused lobes. There is moderate infiltration of extravillous trophoblast (“X-cells”) into the decidua basalis. In contrast to other guenons and cercopithecids that have been described, this placenta was completely devoid of any infarcts. It was severely congested with fetal blood, however. Mossman (1987) has suggested that the cercopithecids have a ‘somewhat trabecular to villous placenta'. This was not really evident in sections of this mature organ although the histologic pictures below will show that some fibrous partitions from the floor extend into the villous tissue; they are covered with trophoblast.

|

Fetal surface of this spot-nosed monkey placenta. |

|

Maternal surface of the placenta. Its nearly bilobed nature is evident from the central portion of membranes. |

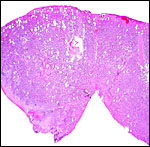

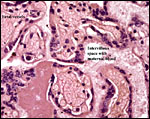

5) Details of fetal/maternal barrier

The placenta differs little from that of other catarrhine primates in having a hemochorial interface. The villi are covered by syncytium and directly face the maternal intervillous blood. Most of the cercopithecid monkeys have a typical discoid (or bidiscoid), hemochorial, villous placenta. Maternal blood circulates around the villi, following “injection” of blood from decidual spiral arterioles. The exchange of nutrients, water, gases, etc. takes place through the syncytiotrophoblast with its finely microvillous “brush” border. The syncytium is post-mitotic and is replenished continuously from underlying cytotrophoblast that is difficult to identify in H&E preparations of term placentas. The syncytium is continuously added to until term. In later gestation, the syncytium has foci of apoptosis, and syncytial “knots” flake off into the intervillous space. Large numbers of these syncytial knots are transported into the maternal lung during pregnancy; at least this is so in human gestations, where the transport has been amply documented. A small amount of calcification occurs in the basal portions of the placenta at term.

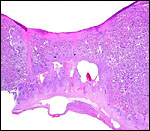

6) Umbilical cord

The cord was 20 cm long and extremely thin (0.2-0.3 cm). It had no noticeable twists. There was no rudimentary allantoic duct, although this is occasionally present in other cercopithecids. This animal's cord is unusual in that it possessed only one umbilical artery. Single umbilical artery (“SUA”) is found in about 1% of human placentas and around 50% of these are stillborn or have some sort of congenital anomaly (Benirschke et al., 2006). No reports have given adequate information of the umbilical cord length of other spot-nosed guenons. Spatz (1968) who has tabulated much information found it to be around 12-14 cm long in other cercopithecids but he did not cite this species. Houston & Hendrickx (1968) and Young (1972) investigated different primates' umbilical cords for the presence of a ‘transverse communicating artery' (“Hyrtl anastomosis”) but they did not have this species available. Our specimen was anomalous in that it had only one artery in numerous cross sections; thus, such an investigation would have been impossible with this specimen. Despite this anomaly, the neonate is thriving.

|

Cross section of this animal's umbilical cord. It has only one umbilical artery (at right). |

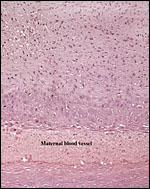

7) Uteroplacental circulation

I am not aware of any publications in this species. It is likely to be similar to that of other cercopithecidae. In some decidual arterioles the arterial wall has been largely replaced by extravillous trophoblast. In others the trophoblast is less obvious.

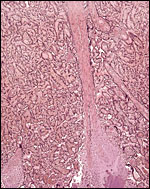

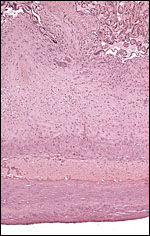

8) Extraplacental membranes

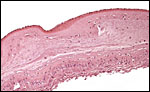

The membranes insert at the margin, are composed of amnion, chorion, a thin layer of extravillous trophoblast and a very small amount of decidua capsularis. Beneath the chorionic plate is this layer of cytotrophoblast that is often markedly vacuolated. I have previously commented upon the absence of atrophied villi in these membranes of catarrhine primates (Benirschke & Miller, 1982) which was also true of this placenta. On the other hand, free fetal vessels were found in portions of the chorion laeve, apparently similar to those of rhesus monkeys and others with bilobed organs. Minimal degrees of decidual necrosis were present at the periphery of this placenta.

|

Chorion laeve with amnion above, fused with the chorion and underlain by some extravillous trophoblast. Very little decidua capsularis. |

|

Chorion laeve with two connective fetal blood vessels. |

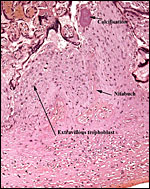

9) Trophoblast external to barrier

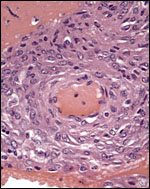

There is no extravillous invasion by trophoblast other than the moderate number of extravillous trophoblast in the decidua basalis; few such cells are found in some spiral arterioles, while others have their walls reconstituted by trophoblast.

|

Spiral arteriole within the small amount of decidua basalis; very rare etravillous trophoblast infiltration is present. |

10) Endometrium

Normal decidua forms in the second half of the cycle and is present throughout gestation. There is a thin decidua basalis with some moderately altered arterioles and moderate trophoblastic ingrowth at the placental base. There are few lymphocytes and macrophages in the decidua basalis and some distension of uterine glands (with secretion) exists. There is a distinct albeit thin and discontinuous layer of Nitabuch's fibrin. Only relatively little decidua basalis was shed with this normally delivered placenta.

11) Various features

There is no subplacenta and no special features are present.

12) Endocrinology

There is no published information.

13) Genetics

The spot-nosed monkey (or white-nosed monkey) has 66 chromosomes and banding patterns have been described in considerable detail (Egozcue, 1969; Caballin et al., 1980; Dugoujon et al., 1981). Some of these authors also discuss the chromosomal evolution of related species and review synonyms of these animals. Thus, the fertile hybridization with C. nictitans and C. ascanius described by Gray (1972) is not surprising as some authors consider them to be subspecies. The following karyotype is that of C.p. petaurista. Note the unusual #32 chromosome pair.

|

Karyotype of female Cercopithecus ascanius schmidti with 2n=66 . |

14) Immunology

There have been no publications and I know of no relevant data on guenons. Many exist in rhesus monkeys and they are discussed in that chapter.

15) Pathological features

I have been unable to find any descriptions of pathological findings in this species. In closely related species, however, recent studies have identified the presence of a new simian immunodeficiency virus, called SIVgsn (Courgnaud et al. 2002 and 2003; Verschoor et al., 2004). As indicated earlier, this placenta was abnormal in having only one umbilical artery.

16) Physiologic data

Cercopithecidae have an uterus simplex and most placentas implant on both the anterior and posterior surfaces. Detailed physiological studies are not reported but Buzzard (2006) has recently compared the cheek pouch storage among guenon species and found that storage in this species is least pronounced. Presumably this relates to their frugivory. I know no other relevant data on spot-nosed guenons. Many exist in rhesus monkeys and will be discussed in that chapter.

17) Other resources

Cell strains of fibrous tissue are available upon request from CRES at the Zoological Society of San Diego by contacting Dr. O. Ryder at oryder@ucsd.edu.

18) Other remarks – What additional Information is needed?

To date neither have early implantations been described, nor are data available on any in situ placenta.

Acknowledgement

The animal photograph and karyotype in this chapter comes from the Zoological Society of San Diego.

References

Benirschke, K., Kaufmann, P. and Baergen, R.N.: The Pathology of the Human Placenta. 5 th ed. Springer, NY, 2006.

Benirschke, K. and Miller, C.J.: Anatomical and functional differences in the placenta of primates. Biol. Reprod. 26:29-53, 1982.

Buzzard, P.J.: Cheek pouch use in relation to interspecific competition and predator risk for three guenon monkeys (Cercopithecus spp.). Primates April 28, 2006.

Caballin, M.R., Miro, R., Ponsa, M., Florit, F., Massa , C. and Egozcue, J.: Banding patterns of the chromosome of Cercopithecus petaurista (Schreber, 1775): comparison with other primate species. Folia Primatol. 34:278-285, 1980.

Courgnaud, V., Salemi, M., Pourrut, X., Mpoudi-Ngole, E., Abela, B., Auzel, P., Bibollet-Ruche, F., Hahn, B., Vandamme, A.M., Delaporte, E. and Peeters, M.: Characterization of a novel simian immunodeficiency virus with a vpu gene from greater spot-nosed monkeys (Cercopithecus nictitans) provides new insights into simian/human immunodeficiency virus phylogeny. J. Virol. 76:8298-8309, 2002.

Courgnaud, V., Abela, B., Pourrut, X., Mpoudi-Ngole, E., Loul, S., Delaporte, E. and Peeters, M.: Identification of a new simian immunodeficiency virus lineage with a vpu gene present among different cercopithecus monkeys (C. mona, C. cephus, and C. nictitans) from Cameroon. J. Virol. 77:12523-12534, 2003.

Dugoujon, J.M., Moro, F. and Larrouv, G.: Cytogenetic study of five species of Cercopithecus. Folia Primatol. 36:310-322, 1981.

Egozcue, J.: Primates. pp.357-389 in, Benirschke, K.: Comparative Mammalian Cytogenetics. Springer-Verlag , NY , 1969.

Geissmann, T.: Twinning frequency in catarrhine monkeys. Human Evolution 3:387-396, 1990.

Gotch, A.F.: Mammals – Their Latin Names Explained. Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset, 1979.

Gray, A.P.: Mammalian Hybrids. A Check-list with Bibliography. 2 nd edition. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux Farnham Royal, Slough , England , 1972.

Hayssen, V., van Tienhoven, A. and van Tienhoven, A.: Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: a Compendium of Species-specific Data. Comstock/Cornell University Press, Ithaca , 1993.

Houston , M.L. and Hendrickx, A.G.: Observations on the vasculature of the baboon placenta ( Papio sp.) with special reference to the transverse communicating artery. Folia Primatol. 9:68-77, 1968.

Mossman, H.W.: Vertebrate Fetal Membranes. MacMillan, Houndmills, 1987.

Puschmann, W. Zootierhaltung. Tiere in Menschlicher Obhut. Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Harri Deutsch, Frankfurt , 2004.

Spatz, W.B.: Nabelschnur-Längen bei Insektivoren und Primaten. Z. Säugetierk. 33:226-239, 1968.

Verschoor, F.J., Fagrouch, Z., Bontjer, I. , Niphius, H. and Heeney, J.L.: A novel simian immunodeficiency virus isolated from a Schmidt's guenon (Cercopithecus ascanius schmidti). J. Gen. Virol. 85:21-24, 2004.

Weigl, R.: Longevity of Mammals in Captivity; From the Living Collections of the World. Schweizbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Nägele & Obermiller). Stuttgart , 2005.

Young, A.: The primate umbilical cord with special reference to the transverse communicating artery. J. Human Evol.1:345-359, 1972.