| |

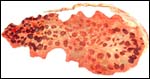

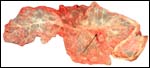

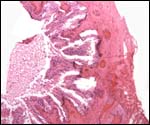

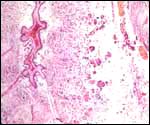

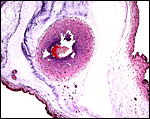

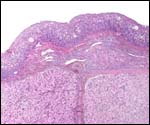

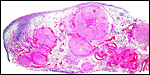

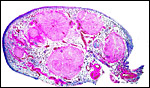

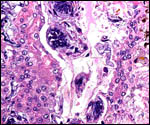

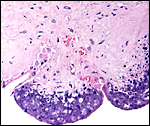

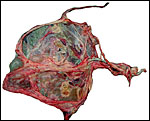

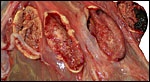

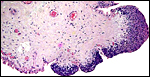

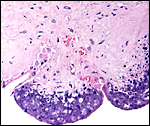

In July, 2003, we had an abortion in a Baringo giraffe. The dam went spontaneously into labor and was known to be ill. The structurally normal male fetus weighed only 19 kg and the small placenta weighed 1,300 g. Most remarkably, it had only 23 cotyledons that were yellow-red and appeared infected. The cord was 34 cm long. Pictures are shown next.

|

Fetal surface of aborted giraffe fetus' placenta. |

| |

|

|

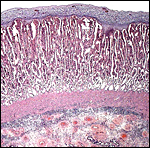

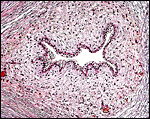

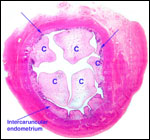

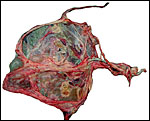

Maternal surface of the same placenta showing the yellow/red cotyledons. |

| |

|

|

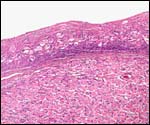

Three apparently degenerating, yellow-discolored cotyledons. |

| |

|

|

Three additional discolored cotyledons. |

| |

|

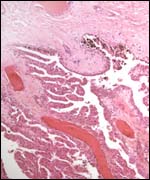

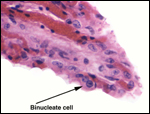

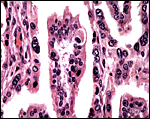

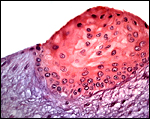

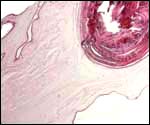

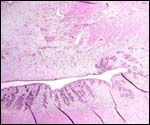

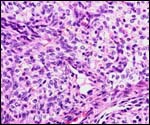

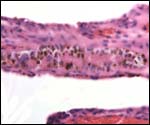

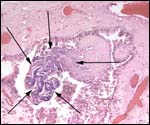

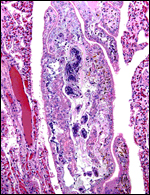

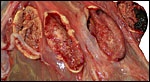

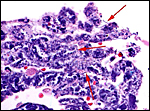

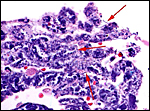

Touch preparations from the cotyledonary surface yielded very long bacilli, with some similarity to actinomyces. Sections of umbilical cord, membranes, fetal lung and testis were all normal and not inflamed or degenerated. The cotyledons, however, had a largely necrotic surface and the same long organisms were identified. Post partum the dam has a vaginal discharge but, while on antibiotics, seems reasonably healthy. Sections are shown next. I speculate that the dam must have had a preexisting endometritis that prevented normal cotyledons to form so that she ended with only 23 and very small cotyledons. That the fetus grew to become 19 kg in size is remarkable. The only similar histology I have encountered is that of a dromedary (see that chapter) in which a stillborn had a largely calcified villous surface that has great similarity to this placenta.

|

Low power view of cotyledonary/villous surface in the Baringo giraffe abortus from San Diego Zoo's Wild Animal Park . The surface is largely necrotic but there is only minimal inflammation and part of the cotyledonary trophoblast (left) is still intact. |

| |

|

|

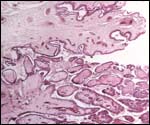

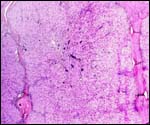

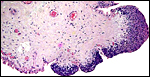

The same cotyledon under higher magnification. There is only minimal inflammation. |

| |

|

|

In between cotyledons debris of this kind is found with the red arrows pointing to some of the many long bacilli. |

| |

|

Murai et al. (2007) have described a large (20x36x20 cm) teratoma of the umbilical cord of a reticulated giraffe two months before birth; the dam died during gestation.

16)

Physiologic data

Many physiologic data, such as hematologic values, blood pressure, and respiration

were compiled by Spinage (1968), and also by Warren (1974). Cerebral blood

pressure is of normal proportion, and the mechanism of prevention of foot

edema, often discussed in the literature, is probably due to a difference

in the structure of blood vessels and connective tissue.

17)

Other resources

Cell lines of many subspecies are stored in the Frozen

Zoo of CRES at the San Diego Zoo. They can be made accessible by contacting

Dr. O. Ryder (oryder@ucsd.edu).

18)

Other remarks - What additional Information is needed?

No implanted placenta has been examined, thus not much is known about

the fetal/maternal interface. Examination of the fetal/maternal interface

would thus be of interest. Since there are so few binucleate trophoblastic

cells, it would also be interesting to know if placental lactogen is produced.

Estrogen determinations during pregnancy would be helpful. Finally, the

status of the endocrine stimulus for the fetal corpora lutea or luteinized

fetal atretica follicles needs clarification.

Acknowledgement

I appreciate very much the help of the pathologists at the San Diego Zoo

in collecting specimens.

References

Deka, B.C., Nath, K.C. and Borgohain, B.N.: Clinical note on the morphology

of the placenta in a giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis). J. Zoo An.

Med. 11:117-118, 1980.

Eschricht,

D.F.: De organis, quae respirationi et nutritioni foetus mammalium inserviunt;

anniversaria (Schultzianis, Havniae 1837). Quoted by Ludwig, 1962.

Fowler,

M.E.: Peracute mortality in captive giraffe. JAVMA 173:1088-1093, 1978.

Gijzen, A.: Das Okapi. (Neue Brehm-Bucherei). A. Ziemsen Verlag. Wittenberg

Lutherstadt, 1959.

Gatesy,

J. and Arctander, P.: Molecular evidence for the phylogenetic affinities

of ruminantia. Chapter 9, pp. 143-170, in Vrba, E.S. and Schaller, G.

B., eds. Antelopes, Deer, and Relatives. Yale University Press, New Haven,

2000.

Gentry,

A.W.: The ruminant radiation. Chapter 2, pp. 11-25, in Vrba, E.S. and

Schaller, G. B., eds. Antelopes, Deer, and Relatives. Yale University

Press, New Haven, 2000.

Gombe,

S., and Kayanja, F.I.B.: Ovarian progestins in Masai giraffe (Giraffa

camelopardalis). J. Reprod. Fert. 40:45-50, 1974.

Gray, A.P.: Mammalian Hybrids. A Check-list with Bibliography. 2nd edition.

Common-

wealth Agricultural Bureaux Farnham Royal, Slough, England, 1972.

Hall-Martin,

A.J. and Rowlands, I.W.: Observations on ovarian structure and development

of the southern giraffe, Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa. S. Afr.

J. Zool. 15:217-221, 1980.

Hall-Martin,

A.J. and Skinner, J.D.: Observations on puberty and pregnancy in female

giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis). S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 8:91-94,

1978.

Hayssen,

V., van Tienhoven, A. and van Tienhoven, A.: Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian

Reproduction: a Compendium of Species-specific Data. Comstock/Cornell

University Press, Ithaca, 1993.

Hösli,

P. and Lang, E.M.: A preliminary note on the chromosomes of the Giraffidae: Giraffa camelopardalis and Okapia johnstoni. Mammalian Chromosomes

Newsletter 11:109-110, 1970.

Hradecky,

P.: Placental morphology in African antelopes and giraffes. Theriogenology

20:725-734, 1983.

Hradecky,

P., Benirschke, K. and Stott, G.G.: Implications of the placental structure

compatibility for interspecies embryo transfer. Theriogenology 28:737-746,

1987.

Kellas,

L.M., van Lennep, E.W. and Amoroso, E.C.: Ovaries of some foetal and prepuberal

giraffes [Giraffa camelopardalis (Linnaeus)]. Nature 181:487-488,

1958.

Koulisher,

L., Tijskens, J. and Mortelmans, J.: Mammalian Cytogenetics. V. The chromosomes

of a female giraffe. Acta Zool. Pathol. Antverp. 52:93-96, 1971.

Lang,

E.M.: Frühgeburt und künstliche Aufzucht einer Giraffe. Schweiz.

Arch. Tierheilk. 97:198-205, 1955.

Loskutoff,

N.M., Walker, L., Ott-Joslin, J.E., Raphael, B.L. and Lasley, B.L.: Urinary

steroid evaluations to monitor ovarian function in exotic ungulates: II.

Comparison between the giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) and the

okapi (Okapia johnstoni). Zoo Biol. 5:331-338, 1986.

Ludwig,

K.S.: Beitrag zum Bau der Giraffenplacenta. Acta anat. 48:206-223, 1962.

Mossman,

H.W.: Vertebrate Fetal Membranes. MacMillan, Houndmills, 1987.

Mossman,

H.W. and Duke, K.L.: Comparative Morphology of the Mammalian Ovary. The

University of Wisconsin Press, 1973.

Murai, A., Yanai, T., Kato, M., Yonemaru, K., Sakai, H. and Masegi, T.: Teratoma of the umbilical cord in a giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata). Vet. Pathol. 44:204-206, 2007.

Owen,

R.: Notes on the birth of the Giraffe at the zoological Society's gardens,

and description of the foetal membranes and of some of the natural and

morbid appearances observed in the dissection of the young animal. Trans.

Zool. Soc. Lond. 3:21-28, 1849. Quoted by Ludwig, 1962.

Reissig,

D.: Elektronenmikroskopische Untersuchungen am Chorionepithel der Giraffenplacenta.

Verh. Anat. Gesellsch. 71:493-498, 1977.

Skinner,

J.D. and Hall-Martin, A.J.: A note on foetal growth and development of

the giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa. J. Zool. 177:73-79,

1975.

Solounias,

N., McGraw, W.S., Hayek, L.-A. and Werdelin, L.: The paleodiet of the

giraffidae. Chapter 6, pp. 84-95, in Vrba, E.S. and Schaller, G. B., eds.

Antelopes, Deer, and Relatives. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2000.

Spinage,

C.A.: The Book of the Giraffe. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1968.

Taylor,

K.M., Hungerford, D.A. and Snyder, R.L.: The chromosomes of four artiodactyls

and one perissodactyl. Mammalian Chromosomes Newsletter 8:233-235, 1967.

Thenius,

E.: Die Giraffen und ihre Vorfahren. Kosmos 63:160-164, 1967.

Vermeesch,

J.R., DeMeurichy, W., van den Berghe, H., Marynen P. and Petit, P.: Differences

in the distribution and nature of the interstitial telomeric (TTAGGG)n

sequences in the chromosomes of the giraffidae, okapi (Okapia johnstoni),

and giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis): evidence for ancestral telomeres

at the okapi polymorphic rob(4;26) fusion site. Cytogenet. Cell Genet.

72:310-315, 1996.

Warren,

J.V.: The physiology of the giraffe. Scientific American 231:96-105, 1974.

|