| |

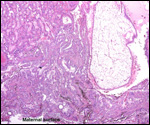

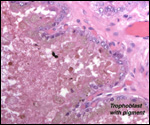

9) Trophoblast external to barrier

Mossman (1987) said the following of specific giant cells at the floor of

the placenta in carnivora: "Most carefully examined carnivore placentas

have been shown to have scattered, usually moderately enlarged cells of

presumed maternal stromal origin alongside the maternal vessels of the zona

intima. These have been called "giant decidual cells" in the hyena

(Wynn & Amoroso, 1964) and cat (Malassiné, 1974), or simply "giant

cells" (Wynn & Björkman, 1968) in the cat and "decidual

cells" (Anderson, 1969) in the dog. Their ultrastructure in the dog

was described in detail by Anderson (1969) and in the cat by Malassiné

(1974). Obviously these cells of carnivores are not in the classical position

of decidua, but their presumed origin from endometrial stroma may justify

associating them tentatively with decidua. They are often not markedly large

(Anderson could not recognize them in paraffin sections of the dog placenta)

and have not been reported in raccoon, mustelids, or bears, possibly, as

Wimsatt (1974) has suggested, because specimen from these have not been

examined by electron microscopy. Both "giant" and "decidual"

cells must be considered tentatively designations until some definite anatomical

or physiological characteristics are discovered that set these cells distinctly

apart and justify a specific name."

Extravillous packets of trophoblast do not exist and the invasion of endometrium

is very superficial, i.e., only through the superficial "compacta"

of the endometrium.

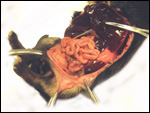

It is of historical interest to note that von Baer (1828) first convincingly

demonstrated that there was no confluence between the maternal and fetal

circulations. He injected a variety of uterine and fetal vessels of animals

with dyes and showed independence of the two vascular systems. This monograph

also provides a beautiful illustration of the dog placenta with partial

separation from the uterus and its broad green marginal regions. For historical

interest it might be nice to learn that this elegant contribution by v.

Baer was dedicated to S.T. v. Soemmerring at his 50th medical anniversary.

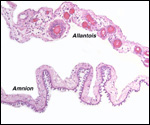

10) Endometrium

Dogs are said to have a "deciduate" placentation but typical decidual

cells are hard to identify, and endometrial glands are present throughout

pregnancy. Thus, no true decidua as in primates is found and there is further

disagreement whether all of the giant cells disappear after delivery of

the placenta.

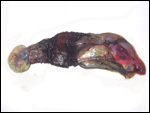

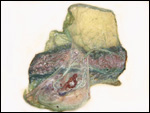

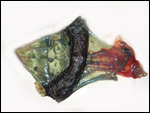

11) Various features

The marginal "hematoma" (green zone) has also been referred to

as "paraplacenta" or a hematophagous organ.

12) Endocrinology

The estrous cycle of dogs averages two per year. Ovulation is spontaneous.

Breeders suggest that the temperature of the pregnant bitch decreases

by about 1 the

day before the delivery is expected. They infer from this that the temperature

drop relates to falling progesterone levels. Actual steroid measurements,

however, are unknown to us. Estrogen is not expected to be produced by

the placenta. Relaxin has apparently been demonstrated. Parturition is

believed to be induced by fetal cortisol and an increased prostaglandin

production by the gravid uterus. The canine corpus luteum is said to be

remarkably resistant to prostaglandin-induced regression. Prostaglandins

are also believed to cause the notorious vomiting in late pregnancy. the

day before the delivery is expected. They infer from this that the temperature

drop relates to falling progesterone levels. Actual steroid measurements,

however, are unknown to us. Estrogen is not expected to be produced by

the placenta. Relaxin has apparently been demonstrated. Parturition is

believed to be induced by fetal cortisol and an increased prostaglandin

production by the gravid uterus. The canine corpus luteum is said to be

remarkably resistant to prostaglandin-induced regression. Prostaglandins

are also believed to cause the notorious vomiting in late pregnancy.

The endocrine patterns of red wolves (Canis rufus) were delineated

in captive animals by fecal and serum analysis (Walker et al., 2002).

I realize that this is a different species, but it seems likely that the

results would be similar to what might be found in domestic dogs. These

investigators studied LH secretion and estrogens, as well as progesterone.

No native testosterone but a more polar androgen metabolite was detected

in males.

Oophorectomy or hypophysectomy during pregnancy leads to pregnancy termination

(Tienhoven, 1983). There are apparently no publications on the placental

production of gonadotropins or estrogens, although Courrier (1945) has

stated that no gonadotropins have been detected in the urine of the pregnant

dog. Histologically, the placenta does not give the impression of being

an endocrine organ.

The fetal/neonatal ovary has a large "interstitial gland".

13) Genetics

The domestic dog has 78 chromosomes. The autosomes are all acrocentrics;

the X chromosome is submetacentric and the Y is a diminutive metacentric

chromosome. Switonski et al. (1996) further defined the fine structure

of chromosomes with excellent G-banding. Hybridization has been reported

to occur with dingo, coyote, wolf, and possibly some foxes. Cats have

not hybridized with dogs, despite rumors in the popular press. A wide

variety of genetic diseases have been recorded in domestic dogs, best

known of which is perhaps the hip dysplasia in shepherds. I strongly recommend the review by Ostrander (2007) that describes in some detail the evolutionary genetic changes that have occurred in the evolution of dogs and its many races.

More recent information on genes and linkage maps are contained in a report

of a symposium on "Advances in Canine and Feline Genomics: Comparative

Genome Anatomy and Genetic Disease" in J. Hered. 94, Issue 1 (January),

2003. It contains a paper on 78XX/77C mosaics.

Several chromosomal errors have been identified in dog. Thus, Switonski

et al. (2000) found trisomy X in an infertile bitch. Her ovaries appeared

to be normal, but the dental arcades showed abnormalities. Sex-reversal

(male to female) was interpreted to be the result of a reciprocal X/A

translocation (Schelling et al., 2001). The bitch had ovotestes, uterus

and epididymis. Two infertile bitches were mosaic 78XX/77/X (Switonski

et al., 2003).

A comprehensive study of dog races, diseases, genetics, neoplasms and other topics has come from Ostrander et al. (2006).

|

Karyotype of male and female domestic dogs. |

14)

Immunology

Despite the occasionally voiced notion that dogs have no blood group antigens,

the studies by Swisher et al. (1962) are a convincing demonstration of

their existence and of the development of iso-antibodies under appropriate

conditions.

The developmental landmarks of the immune system have recently been summarized by Holsapple et al. (2003). Splenic primordial appear on day 28, their “demarcation” occurs on day 45; thymic primordia are recognized on day 28 also, and hematopoiesis in the bone marrow begins on day 45. Proliferation in response to mitogens begins on day 50.

15)

Pathological features

Subinvolution of the placental site has occasionally been described (Beck

& McEntee, 1966). Their illustration suggests to me the retention of

placental tissue in the case that they described. Schlotthauer (1939) described

a choriocarcinoma in a 2-year-old bitch. The involution of the canine placental

site and of the adjacent endometrium has been reviewed in some detail by

McEntee (1990).

There is, of course, a vast literature on pathologic findings in dogs. They

can be accessed through texts on veterinary pathology and from the Armed

Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) in Washington.

16)

Physiological data

No data are known to me.

17) Other resources

Numerous dog-breeding clubs exist and can be identified locally. The Armed

Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) in Washington, DC has an extensive

repository of pathologic lesions from the guard dogs in the military services.

Cell lines of dog and related carnivores are available through CRES, the

research facility of the Zoological Society of San Diego.

18)

Future needs for investigation

Considering that so many placental abnormalities exist in human placentas,

one should expect that similar pathology might occur in other species.

With rare exception these have not been described. Future attention to

such pathologic lesions, especially in stillborn pups, might be rewarding.

The green pigment should be better defined chemically.

References

Anderson,

J.W.: Ultrastructure of the placenta and fetal membranes of the dog. 1.

The placental labyrinth. Anat. Rec. 165:15-36, 1969.

Baer,

C.E.v.: Untersuchungen ueber die Gefaessverbindungen zwischen Mutter und

Frucht in den Saeugethieren. Leopold Voss, Leipzig, 1828.

Beck,

A.M. and McEntee, K.: Subinvolution of placental sites in a postpartum

bitch. A case report. The Cornell Vet. 56:269-277, 1966.

Björkman,

N.: Fine structure of the fetal-maternal area of exchange in the epitheliochorial

and endotheliochorial types of placentation. Acta anat. 86 (Suppl. 1): 1-22,

1973.

Cells

from the zoo's CRES organization via the Web: www.sandiegozoo.org.

Courrier,

R.: Endocrinologie de la Gestation. Paris, 1945.

Duval,

M.: Le placenta des carnassiers. J. Anat. Physiol. Paris 29:249-340,425-465,

663-729, 1893.

Gray, A.P.: Mammalian Hybrids. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Farnham

Royal, Slough, England, 1972.

Holsapple, M.P., West, L.J. and Landreth, K.S.: Species comparison of anatomical and functional immune system development. Birth Defect Res. B 68:321-334, 2003.

Kehrer,

A.: Zur Entwicklung und Ausbildung des Chorions der Placenta zonaria bei

Katze, Hund und Fuchs. Z. Anat. Entwickl.-Gesch. 143:25-42, 1973.

Malassiné,

A.: Evolution ultrastructurale du labyrinthe du placenta de chatte. Anat.

Embryol. 146:1-20, 1974.

McEntee,

K.: Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Mammals. Academic Press, San Diego,

1990.

Mossman,

H.W.: Vertebrate Fetal Membranes. MacMillan, Houndmills 1987.

Ostrander,

E.A., Giger, U. and Lindblad-Toh, K., eds: The Dog and its Genome. Cold Spring Harbor Press,

Cold Spring Harbor, New York, 2006.

Ramsey,

E.M.: The Placenta of Laboratory Animals and Man. Holt, Rinehart and Winston,

New York, 1975).

Schelling, C., Pienkowska, A., Arnold, S., Hauser, B. and Switonski, M.:

A male to female sex-reversed dog with a reciprocal translocation. J.

Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 57:435-438, 2001.

Schlotthauer,

C.F.: Primary neoplasms in the genito-urinary system of dogs: a report

of ten cases. J. Am. Vet. Med. Ass. 95:181, 1939.

Selden,

J.R., Moorhead, P.S., Oehlert, M.L. and Patterson, D.F.: The Giemsa banding

pattern of the canine karyotype. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 15:380, 1975.

Starck,

D.: Lehrbuch der speziellen Zoologie. Band II, Teil 5/2. Säugetiere.

Gustav Fischer, Jena, 1995.

Swisher,

S.N., Young, L.E. and Trabold, N.: In vitro and in vivo studies of the

behavior of canine erythrocyte-isoantibody systems. Ann. NY Acad. Sci.

97:15-25, 1962.

Switonski, M., Reimann, N., Bosma, A.A., Long, S., Bartnitzke, S., Pienkowska,

A., Moreno-Milan, M.M. and Fischer, P. (Committee for the Standardized

Karyotype of the Dog (Canis familiaris): Report of the progress

of standardization of the G-banded canine (Canis familiaris) karyotype.

Chromosome Research 4:306-309, 1996.

Switonski, M., Szczerbal, I., Grewling, J., Antosik, P., Nizanski, W.

and Yang, F.: Two cases of infertile bitches with 78,XX/77,X mosaic karyotypes:

a need for cytogenetic evaluation of dogs with reproductive disorders.

J. Hered. 94:65-68, 2003.

Switonski, M., Godynicki, S., Jackowiak, H., Pienkowska, A., Turczuk-Biertla,

I., Szymas, J., Golinski, P. and Bereszynski, A.: X trisomy in an infertile

bitch: cytogenetic, anatomic, and histologic studies. J. Hered. 91:149-150,

2000.

van

Tienhoven, A.: Reproductive Physiology of Vertebrates. Cornell Univ. Press,

Ithaca, 1983.

Vila,

C., Savolainen, P., Maldonado, J.E., Amorim, I.R., Rice, J.E., Honeycutt,

R., Crandall, K.A., Lundeberg, J. and Wayne, R.K.: Multiple and ancient

origins of the domestic dog. Science 276:1687-1679, 1997.

Walker, S.L., Waddell, W.T. and Goodrowe, K.L.: Reproductive endocrine

patterns in captive female and male red wolves (Canis rufus) assessed

by fecal and serum hormone analysis. Zoo Biol. 21:321-335, 2002.

Wimsatt,

W.A.: Morphogenesis of the fetal membranes and placenta of the black bear,

Ursus americanus (Pallas). Am. J. Anat. 140:471-495, 1974.

Wynn,

R.M. and Amoroso, E.C.: Placentation in the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta

Erxleben), with particular reference to the circulation. Am. J. Anat.

115:327-362, 1964.

Wynn,

R.M. and Björkman, N.: Ultrastructure of the feline placental membranes.

Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 102:34-43, 1968.

Wynn,

R.M. and Corbett, J.R.: Ultrastructure of the canine placenta and amnion.

Am. J. Obstet.Gynecol. 103:878-887, 1969.

|