| (Clicking

on the thumbnail images will launch a new window and a larger version

of the thumbnail.) |

| Last

updated: December 11, 2003. |

Octodon degus

By Andrea Mess & Peter Kaufmann

Order: Rodentia

Suborder: Hystricognathi (sensu Tullberg 1899), as a member of South American hystricognaths, the Caviomorpha

1) General Zoological Data

Systematics: The degu belongs to the rodent suborder Hystricognathi. This group was originally defined by Tullberg in 1899, but its validity was later doubted because of the disjunct distribution into a South American group or Caviomorpha on the one hand (including the North American tree porcupines), and the African hystricognaths on the other (with a few species in Europe and Asia). From the mid -1980's on, phylogenetic studies respecting characters of fetal membranes and placentation support the monophyletic hypothesis of Hystricognathi (Luckett, 1985) and have been accepted by former critics of the concept (Wood, 1985). Moreover, Hystricognathi is well supported by molecular data studies (e.g. Nedbal et al., 1994, Huchon et al., 2000), but the relationships within the group are not that well resolved, and data are often not congruent. For instance, there is no morphological support for Caviomorpha (e.g. McKenna & Bell, 1997), although this clade is supported by molecular data sets. The degu is a member of Octodontidae, an ecomorphologically diverse, but monophyletic family (see Honeycutt et al., 2003), which is poorly studied in regard to placentation. Thus, we refer to Hystricognathi when comparing the degu with relatives. Special attention is given to the guinea pig as the best investigated species of the group.

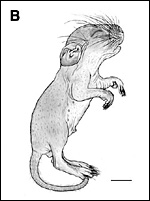

Biological background: Octodon degus is one of the smallest South American hystricognath rodents (Figure 1) and lives in rocky habitat and bush habitat in areas of medium high elevation (up to 1,200 m) native to Chile. Octodon is reported as one of the most common mammals of central Chile with densities of about 40 to 80 individuals per hectare (Nowak, 1999). Regarding body shape and climbing behavior in bushes, trees, and rocks, this agile diurnal species may easily be mistaken for a small squirrel. The tail is not bushy, however, but has a small black brush at the tip (Woods & Boraker, 1975; Nowak, 1999). The degu is grayish to brownish in color, and possesses digits with sharp, curved claws and stiff bristles that extend over the claws. The grinding area of the cheek teeth are shaped like a figure eight, reflecting to the scientific name of the genus (Woods & Boraker, 1975; Nowak, 1999). These teeth are high crowned and ever-growing, forming a powerful tool for manipulating fibrous plant material. The diet includes grass, leaves, bark, herbs, seeds and fruits; the amount of animal material intake is doubtful (Woods & Boraker, 1975; Fulk, 1975, 1976; Nowak, 1999; Veloso & Bozinovic, 2000). The degu lives in small, polygamous colonies with individual territories, characterized by communal burrow systems (Woods & Boraker, 1975; Kleiman et al., 1979; Nowak, 1999). Food and nesting material are accumulated in the burrows. In the wild, Octodon seems to breed once per year, whereas in captive colonies litters occur more frequently. Females of one group may rear their young together in one nest (Weir, 1974; Nowak, 1999). The offspring are born in a relatively advanced developmental condition (Figure 1b), although the exact condition at birth (e.g. if the eyes are open or not) differs in laboratory colonies in different continents (cf. Weir, 1974; Rojas et al., 1982; Nowak, 1999). According to our personal observations, the newborn are kept hidden in their nests for the first one or two weeks of life. Thus, the eyes of such young are usually closed, but could be opened if necessary, e.g. when the surrounding of the nest is disturbed. Lactation is reported to last 2 to 4 weeks, and the medium age of first conception is about 6 months (Weir, 1974; Nowak, 1999). In addition to the references cited, there is a broad range of papers available on Octodon, covering the fields of energetic and nutritional biology, circadian rhythm, thermoregulation, and adaptations in skull morphology and sensory systems. Additional information is available on various degu web sites through Google.com.

Estrous cycle: Octodon does not possess a regular estrous cycle, but it depends on male presence to induce ovulation. Postpartum ovulation takes place, but not regularly (Weir, 1974).

Length of gestation: 87 - 93 days (Weir, 1974).

Litter size: 1 - 10, mean 5 (Weir, 1974), under laboratory conditions, according to our data: 1 - 7, mean 4.

Body weight (non pregnant): 170 to 230 g according to our data.

Fetal weight at full term: about 10 g according to our data.

Weight of placenta and membranes at full term: about 8 g (Roberts & Perry, 1974).

3) Implantation and Formation of the Fetal Membranes

Primary and completely interstitial implantation at the antimesometrial pole of the uterus takes place around day 6 ½ to 7 post conception (Roberts & Perry, 1974). This type of implantation is regarded as a defining character of Hystricognathi (Luckett, 1985).

The yolk sac is characterized by very early and complete inversion (Roberts & Perry, 1974; personal observation). As a striking characteristic of hystricognaths (Luckett, 1985), the abembryonic trophoblast degenerates soon after implantation is finalized, coupled with the inversion of the germ layers at this time (Roberts & Perry, 1974).

Formation of the amniotic cavity takes place on day 12 ½ p.c. The amnionic cavity is formed by cavitation as is usual for hystricognaths (Roberts & Perry, 1974).

Formation of the allantois takes place on day 30 p.c. (Roberts & Perry, 1974).

Formation of the chorioallantoic placenta takes place around day 30 to 35 p.c. (Roberts & Perry, 1974).

As is typical for hystricognaths (see Luckett, 1985), the chorion seems to be restricted exclusively to the chorioallantoic placenta (personal observation).

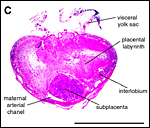

General placental type: Discoidal, labyrinthine, hemomonochorial, chorioallantoic placenta with main placental disc and a special subplacenta as well as a separate yolk sac placenta (cf. Figures 2 to 7).

Allantois: Only used for formation and vascularization of the chorioallantoic placenta (main placenta and subplacenta).

According to investigations of histological serial sections and semi-thin slides (Mess, 2001, 2003; personal observation) as well as the ultrastructural descriptions by King (1992) and Kertschanska, Schroeder, & Kaufmann (1997), the structural organization of the degu's main placenta and the ultrastructure of its barrier mainly correspond to that of the guinea pig. However, some differences exist with regard to the macroscopic organization of the placenta.

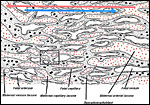

As is typical for hystricognaths, the chorioallantoic main placenta (Figures 2 and 3) consists of a labyrinthine zone (including fetal vessels) in the middle region of the placental disc and a more spongy component (without fetal vessels), that is mainly situated at the outer border of the placental disc, but also found in between parts of the labyrinth (Figure 2). Based on the nomenclature introduced for the closely related guinea pig placenta (Kaufmann & Davidoff, 1977), this area is here recognized as interlobium. Other names for this region are for instance "spongy zone", "trophospongium" or "ectoplacenta".

In the degu, the chorioallantoic placenta is only very moderately lobulated, even in late ontogenetic stages. That means that the labyrinth is not composed of finger-like lobes, each lobe representing its own circulatory unit, nearly completely separated by interlobium, as in most other hystricognaths such as the guinea pig. Instead, the separation of the labyrinth by the interlobium is incomplete in the degu. Folds of the interlobium push out medially from a ring-like outer region of the placental disc, but do reach the center of the placenta and do not fully separate parts of the labyrinth (Figure 2). Thus, the labyrinthine parts of the placenta are largely joined together (Figure 3). Additionally, in the area of the central excavation, a layer of interlobium is present that appears to divide the labyrinth into two halves (Figure 2).

Besides the moderate lobulation of the degu placenta, the fine structure and the vascular architecture of the fetomaternal exchange area, the labyrinth, do not differ from other hystricognaths:

• the maternal blood flows from a central arterial lacuna (Figures 2 and 3) centrifugally via a web-like system of trophoblast-lined blood lacunae (Figures 4 and 5) to the periphery of the labyrinth, i.e. the spongy zone or interlobium, where the blood is drained by a web of venous lacunae (Figure 3);

• the fetal blood enters the same region via several fetal arterioles (Figure 3), located at the lobular surface, i.e. at the border between labyrinth and interlobium; there they branch into radially oriented capillaries which lead the fetal blood centripetally; the blood is collected by fetal venules in the center of the labyrinth (see Figure 3) and then returned back to the embryo by the umbilical vein.

As a result of the very moderate lobulation of the degu placenta, the blood flow arrangement does not represent a perfect counter-current exchanger as in the guinea pig. In contrast, the system in the degu is characterized by the fact that the exchange vessels (fetal capillaries and maternal capillary lacunae) do not span similar distances all over the placenta, but differ in length depending on their place in the placenta. Usually, the capillary length is shorter in regions where the interlobium is protruding medially, whereas it is longer in the outer parts of the labyrinthine lobes (see Figure 2). The phylogenetic interpretation suggests that a purely lobulated condition of the placenta represents the ancient condition of hystricognaths (plesiomorphic character state), from which highly lobulated placentas evolved (Mess, 2003).

The fetal/maternal barrier of the degu is hemomonochorial (Figure 6), as in all hystricognaths. The maternal and fetal blood systems are separated by a layer of syncytiotrophoblast which is situated in between the maternal capillary lacunae and the fetal capillaries (Figure 5). The latter possess fetal endothelium as well as a basal lamina towards the syncytiotrophoblastic side (Figure 6). The fetal capillaries are not fenestrated (Figure 6). Intervening connective tissue in the trophoblastic region is rare, and the syncytiotrophoblast is characteristically thin (Figures 5 and 6), as in other hystricognaths (see Kaufmann & Davidoff, 1977; Mess, 2003).

Cytotrophoblast can be found throughout the placenta only in the first weeks of pregnancy. In later stages, cytotrophoblast occurs in the outer region of the interlobium or spongy zone of the main placenta. In addition, the so-called subplacenta (see below) consists mainly of cytotrophoblast, which also continues into late ontogenetic stages.

6)

Umbilical Cord

The umbilical cord is similar in position to that of the guinea pig (Figures

2 and 3). It consists of two main arteries and one large vein which returns

the oxygenated blood back to the fetus (Figure 3).

7) Uteroplacental Circulation

A group of arteries from the mesometrium enters the chorioallantoic placenta.

These are mostly situated in close proximity to the subplacenta (Figures

2 and 3), where trophoblast invasion of the arterial wall has taken place.

The invasion results in maternal arterial blood channels or lacunae that

are lined by trophoblast rather than by maternal endothelium, i.e. a hemochorial

condition of placentation. As mentioned for the guinea pig, also in Octodon

the cytotrophoblast from the subplacenta can be traced towards these arterial

channels, particularly in early to mid- pregnancy stages. This finding

suggests that the subplacenta in caviomorph rodents serves as the source

of interstitial and vascular trophoblast invasion. In the maternal venous

system of the degu, a basal ring of veins (present in the guinea pig)

does not occur (cf. Figures 2 and 3).

8) Extraplacental Membranes

As in the guinea pig, the yolk sac replaces the thin, non-placental parts

of the blastocystic trophoblast vesicle. Thus, together with the chorioallantoic

placenta, the visceral yolk sac placenta forms the regions that are most

responsible for fetomaternal exchange processes. Because of the inversion

of the germ layers in hystricognaths, the visceral yolk sac is endodermally

covered, and in intimate contact with the endometrial surface epithelium

of the uterus, and it is fetally vascularized towards its inner side (Figures

2, 3 and 7). Near the attachment to the umbilical cord, the visceral yolk

sac is highly folded, whereas other regions are more smooth (Figures 2

and 3). The folds are in close contact with the uterine endometrium on

the one hand (Figure 7) as well as with the parietal yolk sac that covers

the chorioallantoic placenta on the other (Figure 2). Medial to the highly

folded region, the yolk sac splanchnopleure possesses a ring-like artery

that is associated with a small network of capillaries (Figure 8). Although

this capillary band is not very prominent, it is similar in position to

that of other hystricognaths. Thus, the presence of a so called fibrovascular

ring, i.e. one of the defining characters of Hystricognathi according

to Luckett (1985), can be confirmed for Octodon (Mess, submitted).

9) Trophoblast External to Barrier

As mentioned above, cytotrophoblast can be found especially in the subplacenta

as well as in the outer regions of the interlobium, even in advanced ontogenetic

stages. Thus, the condition of the degu is very likely similar to that

of the guinea pig.

10) Endometrium

Although not studied in detail as yet, initial investigations found similar

conditions to the guinea pig. However, as one characteristic difference,

the primary uterine cavity remains present in later ontogenetic stages

in the degu. No data are available, however, on the general aspects of

decidualization. That of rodent endometrium in general has been covered

in detail by Abrahamson & Zorn (1993).

11) Various Features

As in all caviomorph rodents, a distinct subplacenta can be found beneath

the chorioallantoic main placenta of the degu. We did not find differences

when comparing them to the subplacenta of the guinea pig (for details

of the latter see Kaufmann & Davidoff, 1977). In short, the subplacenta

is composed of

• a broad and complex folded layer consisting of cytotrophoblast

with an incomplete layer of syncytiotrophoblast towards the uterine side;

• some connective tissue cells which embed scarce fetal capillaries

underneath the cytotrophoblast;

• and a web-like system of maternal lacunae penetrating the syncytiotrophoblast.

In the guinea pig, the maternal blood flow in these lacunae ceases a few

weeks post conception. Fetal capillarization of the subplacenta starts

only thereafter. Consequently, the subplacenta is in no stage of pregnancy

supplied simultaneously by both maternal and fetal blood flows and, therefore,

it cannot serve as an exchange organ. The situation in the degu seems

to be similar, although not as many stages are available for study. The

subplacenta, however, is at least partly present in a near-term stage

of the degu, whereas it degenerates a few days prior to parturition and

leaves a mass of cellular detritus at the latter site of placental separation

in the guinea pig.

The functional relevance of the subplacenta is still a mystery. Structural

data suggest a mainly secretory function. As the main source of cytotrophoblast

throughout pregnancy, its contribution to trophoblast invasion must be

discussed (see guinea pig). However, the presence of a subplacenta appears

to be a derived character of Hystricognathi (Luckett, 1985).

12) Endocrinology

No data are available.

13) Genetics

The chromosomal diversity within the family Octodontidae is extensive,

ranging from a diploid number of 2N = 38 to 102, but the plesiomorphic

condition for the family range between 2N = 46 to 58 (Honeycutt et al.,

2003). Octodon degus possesses a diploid number of 2N = 58 with a genome

size of 8.6 picograms (Honeycutt et al., 2003; Fernandez, 1968). Prenatal

meiosis was studied by Rojas et al. (1984).

14) Immunology

No relevant studies are known to us.

15) Pathological Features

Degus are susceptible to develop diabetes, especially when fed sugar-containing

foods. Oral/dental problems are other problems in captivity and perhaps

vitamin C supplements are needed. Broken tails occur frequently. Cataracts

are perhaps related to inbreeding.

16) Physiological Data

Not many data are available. Allocation of energy for reproduction in

Octodon is linked to the environmental quality of food. Increase of food

intake to compensate for the higher energy demands of lactation can be

observed especially when high-quality food is available, as compared with

gestation or non-breeding periods (Veloso & Bozinovic, 2000).

17) Other Resources

Regrettably, we have no cell lines of Degu at CRES

in the San Diego Zoo and we are not aware of their existence elsewhere.

18) Other Remarks - What additional information is needed?

Regarding the structure of placenta and fetal membranes, the degu fits

well into the hystricognaths. However, the chorioallantoic placenta is

characteristically less lobulated than in most other members of the group,

followed by an imperfect organization of counter-current exchange units

within the labyrinth. Thus, in this respect the degu can be used as a

model for the placental organization in the stem species pattern of Hystricognathi,

possibly representing a condition from which the highly lobulated placentas

such as that of the guinea pig evolved.

Acknowledgement

The data on the fine structure of the placenta were based on a degu breeding

colony provided by Dr. Hobe Schroeder, Hamburg, Germany. The histological

sections are derived from a colony housed at the universities of Tübingen

and Berlin, going back to individuals from the Zoological Garden in Stuttgart,

the Wilhelma. Robert Asher helped with the English. We thank all involved

colleagues and institutions.

References

Abrahamson, P.A. and Zorn, T.M.T.: Implantation and decidualization in

rodents. J. Exp. Zool. 266:603-628, 1993.

Fernandez, R.: Karyotype of Octodon degus (Rodentia ochotonidae)(Molina 1782). Arch. Biol. Med. Exp. (Santiago) 5:33-37, 1968. (In Spanish).

Fulk, G.W.: Population ecology of rodents

in the semiarid shrublands of Chile. Occas Papers Mus. Texas Tech. Univ.

33, 1975.

Fulk, G.W.: Notes on the activity, reproduction, and social behaviour

of Octodon degus. J. Mamm. 57: 495-505, 1976.

Honeycutt, R.L., Rowe, D.L., and Gallardo, M.H.: Molecular systematics

of the South American caviomorph rodents: relationships among species

and genera in the family Octodontidae. Mol. Phyl. Evo. 26: 476-489, 2003.

Huchon, D., Catzeflis, F.M. and Douzery, E.J.P.: Variance of molecular

datings, evolution of rodents and the phylogenetic affinities between

Ctenodactylidae and Hystricognathi. Proc. Roy. Soc. London B 267: 393-402,

2000.

Kaufmann, P. and Davidoff, M.: The guinea-pig placenta. Adv. Anat. Embryol.

Cell Biol. 53: 1-91, 1977.

Kertschanska, S., Schroeder, H., and Kaufmann, P.: The ultrastructure

of the trophoblast layer of the degu (Octodon degus) placenta:

re-evaluation of the 'channel problem'. Placenta 18: 219-225, 1997.

King, B.F.: Ultrastructural evidence for transtrophoblastic channels in

the hemomonochorial placenta of the degu (Octodon degus). Placenta

13: 35-41, 1992.

Kleiman, D.G., Eisenberg, J.F. and Maliniak, E.: Reproductive Parameters

and productivity of caviomorph rodents. In: Eisenberg JF: Vertebrate ecology

in the northern neotropics. Smithsonian Inst. Press, Washington DC: 173-183,

1979.

Luckett, W.P.: Superordinal and intraordinal affinities of rodents. Developmental

evidence from the dentition and placentation. In: Luckett, W.P. and Hartenberger,

J.-L. (eds.): Evolutionary Relationships among Rodents. NATO ASI-Series

92. Plenum Press. New York: 227-276, 1985.

Mess, A.: Evolutionary differentiation of placental organisation in hystricognath

rodents. In: Denys, C., Granjon, L., and Poulet, A. (eds.): African Small

Mammals. IRD Éditions, collection Colloques et séminaires.

Paris: 279-292, 2001.

Mess, A.: Evolutionary transformations of chorioallantoic placental characters

in Rodentia with special reference to hystricognath species. J. Exp. Zool.

299A: 78-98, 2003.

Mess, A.: The fibrovascualar ring: A synapomorphy of hystricognath Rodentia

newly described in Petromus typicus and Octodon degus.

Belg. J. Zool., submitted.

McKenna, M.C. and Bell, S.K.: Classification of mammals above the species

level. Columbia University Press. New York, 1997.

Nedbal, M.A., Allard, M.W. and Honeycutt, R.L.: Molecular systematics

of hystricognath rodents. Evidence from the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene.

Mol. Phylog. Evol. 3: 206-220, 1994.

Novak, R.M.: Walker's Mammals of the World. 6th Edition. Johns Hopkins

University Press. Baltimore, 1999.

Roberts, C.M. and Perry, J.S.: Hystricomorph embryology. Symp. Zool. Soc.

London 34: 333-360, 1974.

Rojas, M.A., Montenegro, M.A. and Morales, B.: Embryologic development

of the degu, Octodon degus. J. Reprod. Fert. 66: 31-38, 1982.

Rojas, M.A., Morales, B. and Esponda, P.: Foetal meiosis in the testis

of the rodent Octodon degus. Int. J. Androl. 7:529-541, 1984.

Tullberg,

T.: Ueber das System der Nagethiere. Eine phylogenetische Studie. Akademische

Buchdruckerei. Upsala, 1899.

Veloso, C. and Bozinovic, F.: Effect of food quality on the energetics

of reproduction in a precocial rodent, Octodon degus. J. Mamm.

81: 971-978, 2000.

Weir, B.J.: Reproductive characteristics of hystricomorph rodents. Symp.

Zool. Soc. London 34:265-301, 1974.

Wood, A.E.: The relationships, origin and dispersal of the hystricognathous

rodents. In: Luckett, W.P. and Hartenberger, J.-L. (eds.): Evolutionary

Relationships among Rodents. NATO ASI-Series 92. Plenum Press. New York:

475-513, 1985.

Woods, C.A. and Boraker, D.K.: Octodon degus. Mammalian Species

67, 1975.