| |

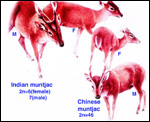

The chromosome number of cervidae is variable. The usually high chromosomal

number in many deer species (around 2n=70) presumably reflects their closer

relationships, while a few "outliers" are also somewhat removed

from the mainstream of cervidae (see Yang et al, 1997). We have established

the following chromosome numbers: Moose (70); Axis deer - chital (66); Hog

deer (68); Roe deer (70); Barasingha deer (56); Red deer (68); Sambar deer

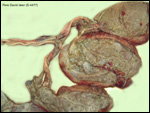

60; 64-65); Fallow deer - Dama (68); Père David's deer (68); Chinese

water deer (Hydropotes inernis) (70); Red brocket deer (Mazama)

(50); Reindeer (70); Pudu (70); White-tailed deer (70); Mule deer (70);

Chinese muntjac (46); Indian muntjac (6/7) [see Hsu & Benirschke]. Since

then, numerous chromosomal banding studies have been done on some of these

species and additional species have also been studied: Tufted deer (Elaphodus

cephalophus) 2n=46-48 (Shi et al., 1991); white-lipped deer (Cervus

albirostris Przewalski) 2n=66 (Wang et al., 1982), and several other muntjacs.

Eld's deer (Cervus eldi) has 2n=58 (Neitzel, 1979, she also lists

another group of deer species). Sika deer (Cervus nippon hortulorum Swinhoe)

has 2n=64-68 (Gustavsson & Sundt, 1969). Another complete listing may

be found in Groves & Grubb (1987).

Evolutionary relationships have been discussed at the beginning of this

chapter. Modern studies are beginning to provide further insight into disputed

areas. Thus, the mtDNA of muntjacs was explored by Lan & Shi (1993).

Repetitive DNA of cervids was used for evolutionary questions by Bogenberger

et al. (1987). Chromosome "painting" led to a better understanding

of muntjac chromosomal fusions (Yang et al., 1995). mtDNA was used in studying

hybrids between mule and white-tailed deer (Carr et al, 1986), and so forth.

Genetic heterozygosity positively influenced fetal size and growth in white-tailed

deer, while number of fetuses correlated negatively (Cothran et al., 1983).

14) Immunology

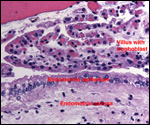

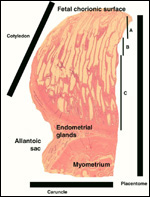

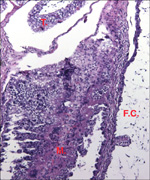

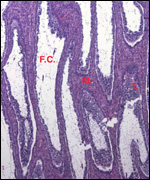

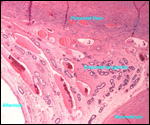

Lymphocytic infiltration of the uterine mucosa/epithelium is a frequent,

if not regular, feature of ruminant uteri. Lee et al. (1995) studied this

in six species of deer. They found a significant cellular increase to occur

from early implantation to mid-gestation. They observed also that the size

of granules of these cells varies greatly and that they increase with gestation.

The investigators observed that these lymphocytes tend to be close to regions

where the trophoblastic binucleated cells fuse with the endometrial epithelium.

Here they produce the trinucleate cells and give up their granules. The

precise reason for these changes remains unknown but "immune recognition" is suspected..

15)

Pathological features

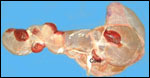

Fetal demise of one of twins has been described in an elk uterus (Saunders,

1955), and Mansell & Cringan (1968) found two dead female fetuses

with a live female triplet in the uterus of a white-tailed deer. The dead

fetuses were enclosed in a single chorion (? monozygotic) and their cotyledons

had detached. They referred to other cases of this fetal absorption and

attributed it to poor nutrition. We have seen this in axis deer and found

no good explanation for the demise.

Major die-offs can occur in island deer due to overcrowding. This was

described for sika deer by Christian et al. (1960). In Texas, abnormal

antler growth of white-tailed deer was the result of hypogonadism, presumed

to result from some poison (Taylor et al, 1964).

Numerous infections have been described in a variety of deer: Toxoplasmosis

in mule deer (Dubey, 1982); Theileria cervi infection in white-tailed

deer (Schaeffler, 1963); Pneumostrongylus tenuis infection of white-tailed

deer (Anderson, 1965), and others. Most important at present is the transmission

of the spirochetal organism Borrelia burgdorferi that causes Lyme

disease and is transmitted from wild mice to man by the deer tick Amblyomma

americanum (e.g. Ebel et al., 2000).

Ratcliffe (1968) reported abnormal antler growth and "wasting" in captive white-tailed deer and related it to abnormal pituitary/adrenal

activity. Trophoblastic tumors have not been described, nor are ascending

intrauterine infections features of cervid gestations.

The San Diego Zoo has traditionally held many cervid species and, consequently,

Griner (1983) gathered much pathological material. Most deaths he recorded

were due to trauma, anesthesia, fracture, fights and old age. Dental disease

was not uncommon in captivity and outbreaks of malignant catarrhal fever

and of blue tongue virus infection were recorded. Only two congenital

heart diseases, one cleft palate and one congenital goiter were observed

as anomalies, and very rare neoplasms (one lymphosarcoma; a biliary carcinoma

in an axis deer, even though deer have no gall bladder) were found. Some

parasites posed a continued problem, but reproductive pathology occurred

rarely.

16) Physiological data

The placenta of some deer species produces a pregnancy-specific protein

B PSPB) which Huang and colleagues (1999) found to be similar, in preparations

from moose and elk, to that extracted from cow and sheep placentas. The

growth of mule deer fetuses and embryos was methodically recorded by Hudson & Browman (1959). Serum protein profiles of white-tailed and mule

deer were studied by Cowan & Johnston (1962). They found great similarity

in quantities, but different electrophoretic mobility in these sympatric Odocoileus species.

I am not aware of any studies of blood flow, blood volume, or blood pressures

records. It is well known, however, that many deer species have a physiologic

tendency to develop sickled erythrocytes. In contrast to human sickle

cell anemia patients whose sickling occurs in oxygen-poor environments,

that of deer species is initiated by increased oxygenation. The sickle

cells are very similar to human sickled red blood cells, with tactoids

and similar shapes, but there is no disease associated with deer sickling.

It is due to hemoglobin polymorphism. (Undritz et al., 1960; Pritchard

et al., 1963; Naik et al., 1964; Kitchen et al., 1964).

17)

Other resources

For a wide variety of cervid species the "Frozen Zoo" of CRES

at San Diego Zoo possesses fibroblast cell lines and most have had chromosomal

analysis.

18) Other relevant features and information needed in future

Several species of deer have become farm animals, especially so with the

advent of a complete understanding of their reproductive physiology. Thus,

Fletcher (2001) gives examples of farming of Cervus elaphus, C.

e. canadensis, Dama dama and D. d. mesopotamica, with

successful embryo transfer and other artificial breeding techniques. We

know too little of the endocrinology and cord lengths. Also, do placental

abnormalities occur?

References

Aitken, R.J.: Ultrastructure of the blastocyst and endometrium of the

roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) during delayed implantation. J.

Anat. 119:369-384, 1975.

Aitken,

R.J., Burton, J., Hawkins, J., Kerr-Wilson, R., Short, R.V. and Steven,

D.H.: Histological and ultrastructural changes in the blastocyst and reproductive

tract of the roe deer, Capreolus capreolus, during delayed implantation.

J. Reprod. Fertile. 34:481-493, 1973.

Anderson,

R.C.: The development of Pneumostrongylus tenuis in the central

nervous system of white-tailed deer. Path. Vet. 2:360-379, 1965.

Bogenberger,

J.M., Neitzel, H. and Fittler, F.: A highly repetitive DNA component common

to all Cervidae: its organization and chromosomal distribution during

evolution. Chromosoma 95:154-161, 1987.

Carr,

S.M., Ballinger, S.W., Derr, J.N., Blankenship, L.H. and Bickham, J.W.:

Mitochondrial DNA analysis of hybridization between sympatric white-tailed

deer and mule deer in west Texas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:9576-9580,

1986.

Cell

lines are available from CRES at the San Diego Zoo under: www.sandiegozoo.org

Chapman,

D.I. and Dansie, O.: Unilateral implantation in the muntjac deer. J. Zool.

Lond. 159:534-536, 1969.

Christian,

J.J., Flyger, V. and Davis, D.E.: Factors in the mass mortality of a herd

of sika deer, Cervus nippon. Chesapeake Sci. 1:79-95, 1960.

Cothran,

E.G., Chesser, R.K., Smith, M.H. and Johns, P.E.: Influences of genetic

variability and maternal factors on fetal growth in white-tailed deer.

Evolution 37:282-291, 1983.

Cowan,

I.M. and Johnston, P.A.: Blood serum protein variations at the species

and subspecies level in deer of the genus Odocoileus. Systematic

Zool. 11:131-138, 1962.

Dubey,

J.P.: Isolation of encysted Toxoplasma gondii from muscles of mule

deer in Montana. JAMA 181:1535, 1982.

Ebel,

G.D., Campbell, E.N., Goethert, H.K., Spielman, A. and Telford, S.R.:

Enzootic transmission of deer tick virus in New England and Wisconsin

sites. Amer. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 63:36-42, 2000.

Fletcher,

T.J.: Deer: New domestic farm animals defined by controlled breeding.

In press, 2001.

Gadsby,

J.E., Heap, R.B. and Burton, R.D.: Oestrogen production by blastocyst

and early embryonic tissue of various species. J. Reprod. Fertil. 60:409-417,

1980.

Gray,

A.P.: Mammalian Hybrids. Second edition. A Check-List with Bibliography.

Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Farnham Royal, Slough, UK, 1972.

Griner,

L.A.: Pathology of Zoo Animals. Zoological Society of San Diego, 1983.

Groves,

C.P. and Grubb, P.: Relationships of living deer. In, Biology and Management

of the Cervidae. C.M. Wemmer, ed. Smithsonian Inst. Press, Washington,

1987, pp. 21-59.

Gustavsson, I. And Sundt, C.O.: Three polymorphic chromosome systems of

centric fusion type in a population of Manchurian Sika deer (Cervus nippon

hortulorum Swinhoe). Chromosoma 28:245-254, 1969.

Hamilton,

W.J., Harrison, R.J. and Young, B.A.: Aspects of placentation in certain

Cervidae. J. Anatomy 94:1-33, 1960.

Harrison,

R.J. and Hamilton, W.J.: The reproductive tract and the placenta and membranes

of Père David's deer (Elaphurus davidianus Milne Edwards).

J. Anat. 86:203-224, 1952.

Hsu,

T.C. and Benirschke, K.: An Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes. Springer-Verlag,

New York, 1975.

Huang,

F., Cockrell, D.C., Stephenson, T.R., Noyes, J.H. and Sasser, R.G.: Isolation,

purification, and characterization of pregnancy-specific protein B from

elk and moose placenta. Biol. Reprod. 61:1056-1061, 1999.

Hudson,

P. and Browman, L.G.: Embryonic and fetal development of the mule deer.

J. Wildlife Manag. 23:295-304, 1959.

Kitchen,

H., Putnam, F.W. and Taylor, W.J.: Hemoglobin polymorphism: Its relation

to sickling of erythrocytes in white-tailed deer. Science 144:1237-1239,

1964.

Kurnosov,

K.M.: Interfetal placental connections of the elk in embryonic parabiosis.

Proc. Akad. Nauk. SSR Doklady, Biol. Sect. 142:92-94, 1962 (in English).

Lan,

H. and Shi, L.: Restricted endonuclease analysis of mitochondrial DNA

of muntjac and related deer. In, Deer of China, N. Ohtaishi and H.-I.

Sheng, eds. Elsevier Science Publ., 1993.

Lawn,

A.M., Chiquoine, A.D. and Amoroso, E.C.: The development of the placenta

in the sheep and goat: an electronmicroscope study. J. Anat. 105:557-578,

1969.

Lee,

C.S., Gogolin-Ewens, K. and Brandon, M.R.: Comparative studies on the

distribution of binucleate cells in the placentae of the deer and cow

using monoclonal antibody, SBU-3. J. Anat. 147:163-179, 1986.

Lee,

C.S., Wooding, F.B. and Morgan, G.: Quantitative analysis of intraepithelial

large granular lymphocyte distribution and maternofetal cellular interactions

in the synepithelichorial placenta of the deer. J. Anat. 187:445-460,

1995.

McMahon,

C.D., Fisher, M.W., Mockett, B.G. and Littlejohn, R.P.: Embryo development

and placentome formation during early pregnancy in red deer. Reprod. Fertil.

Dev. 9:723-730, 1997.

Mansell,

W.D. and Cringan, A.T.: A further instance of fetal atrophy in white-tailed

deer. Canad. J. Zool. 46:33-34, 1968.

Miyamoto,

M.M., Kraus, F. and Ryder, O.A.: Phylogeny and evolution of antlered deer

determined from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

87:6127-6131, 1990.

Mossman,

H.W.: Vertebrate Fetal Membranes. MacMillan, Houndmills, 1987.

Naik,

S.N., Bhatia, H.M., Baxi, A.J. and Naik, P.V.: Hematological study of

Indian spotted deer (Axis deer). J. Exper. Zool. 155:231-236, 1964.

Neitzel,

H.: Chromosomenevolution in der Familie der Hirsche (Cervidae).

Bongo 3:27-38, 1979.

Nowak,

R.M. and Paradiso, J.L.: Walker's Mammals of the World, Vol. II. 4th edition.

The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1983.

Plotka,

E.D.: Deer. In, Encyclopedia of Reproduction. E. Knobil and J.D. Neill,

eds. Academic Press, San Diego 1998, Vol. I, pp.842-857.

Pritchard,

W.R., Malewitz, T.D. and Kitchen, H.: Studies on the mechanism of sickling

of deer erythrocytes. Exp. Molec. Pathol. 2:173-182, 1963.

Puschmann,

W.: Zootierhaltung. Vol. 2, Säugetiere. VEB Deutscher Landwirtschaftsverlag,

Berlin, 1989.

Randi,

E., Mucci, N., Claro-Hergueta, F., Bonnet, A. and Douzery, E.J.P.: A mitochondrial

DNA control region phylogeny of the Cervinae: speciation in Cervus and

implications for conservation. Animal Conserv. 4:1-11, 2001.

Ratcliffe:

Environment, behavior and disease: Observations and experiments at the

Philadelphia Zoological Garden. Trans. & Studies Coll. Physic. Philadelphia

36:7-21, 1968.

Saunders,

J.K.: Fetus in yearling cow elk, Cervus canadensis. J. Mammal.

36:145, 1955.

Schaeffler,

W.F.: Serologic tests for Theileria cervi in white-tailed deer

and for other species of Theileria in cattle and sheep. Amer. J.

Vet. Res. 24:784-791, 1963.

Shi,

L., Ye, Y., Duax, X.: Comparative cytogenetic studies on the red muntjac,

Chinese muntjac, and their F1 hybrids. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 26:22-27,

1980.

Shi,

L. and Pathak, S.: Gametogenesis in a male Indian muntjac x Chinese muntjac

hybrid. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 30:152-156, 1981.

Shi,

L., Yang, F. and Kumamoto, A.: The chromosomes of tufted deer (Elaphodus

cephalophus) Cytogenet. Cell. Genet. 56:189-192, 1991.

Sinha,

A.A., Seal, U.S., Erickson, A.W. and Mossman, H.W.: Morphogenesis of the

fetal membranes of the white-tailed deer. Amer. J. Anat. 126:201-242,

1969.

Sinha,

A.A., Seal, U.S., Erickson, A.W.: Ultrastructure of the amnion and amniotic

plaques of the white-tailed deer. Amer. J. Anat. 127:369-396, 1970.

Taylor,

D.O.N., Thomas, J.W. and Marburger, R.G.: Abnormal antler growth associated

with hypogonadism in white-tailed deer in Texas. Amer. J. Vet. Res. 25:179-185,

1964.

Undritz,

E., Betke, K. and Lehmann, H.: Sickling phenomenon in deer. Nature 187:333-334,

1960.

Vrba,

E.S. and Schaller, G.B., eds.: Antelopes, Deer, and Relatives. Fossil

Record, Behavioral Ecology, Systematics, and Conservation. Yale University

Press, New Haven, 2000.

Wang,

Z., Du, D.R., Xu, J. and Che, Q.: Karyotype, C-banding and G-banding patterns

of white-lipped deer (Cervus albirostris Przewalski). Acta Zool.

Sin. 28:250-255, 1982.(in Chinese).

Weldon,

W.F.R.: Note on placentation of Tetraceros quadricornis. Proc.

Zool. Soc. London pp.2-4, 1884. (Cited by Mossman, 1987).

Wooding,

F.B.: The role of the binucleate cell in ruminant placental structure.

J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 31:31-39, 1982.

Wooding,

F.B.: Frequency and localization of binucleate cells in the placentomes

of ruminants. Placenta 4:527-539, 1983.

Wooding,

F.B., Morgan, G. and Adam, C.L.: Structure and function in the ruminant

synepitheliochorial placenta: central role of the trophoblast binucleate

cell in deer. Microsc. Res. Tech. 38:88-99, 1997.

Wurster,

D.H. and Benirschke, K.: Chromosome studies in some deer, the springbok,

and the pronghorn, with notes on placentation in deer. Cytologia 32:273-285,

1967.

Yang, F., Carter, N.P., Shi, L. and Ferguson-Smith, M.A.: A comparative

study of karyotypes of muntjacs by chromosome painting. Chromosoma 103:642-652,

1995.

Yang,

E., O'Brien, P.C.M., Wienberg, J., Neitzel, H., Kin, C.C. and Ferguson-Smith,

M.A.: Chromosomal evolution of the Chinese muntjac (Muntjacus reevesi).

Chromosoma 106:37-43, 1997.

|