| (Clicking

on the thumbnail images will launch a new window and a larger version

of the thumbnail.) |

| Last updated: May 8, 2004. |

Eulemur fulvus collaris

Order: Primates

Family: Lemuridae

1) General Zoological Data

These lemurs used to be called “brown lemurs” or Lemur fulvus collaris .

The usage of “ Eulemur “ for this group of animals that includes the mongoose lemur, black lemur and crowned lemur as well was chosen by Simons & Rumpler (1988) to distinguish them from ring-tailed lemurs on anatomical grounds. Others disagree with this concept, as is discussed by Nowak (1999). There are several subspecies of collared brown lemurs, all being endangered animals now. A flourishing colony of these animals exists at the Duke Primate Research Center and karyotypes of several animals of that colony have shown a chromosomal polymorphism of 2n=50 to 2n=52. According to its manager, Dean Gibson, the animals with 2n=50 have a significantly lighter, often near-white collar, but then the species is described as being variable in coloration anyway (Nowak, 1999). More than other lemurs, perhaps, this species of the South-East of the Malagasy Island has been described as being mostly arboreal, rarely descending to the ground. Captive management is described for lemurs in general by Puschmann (1989). Adults weigh between 2 and 4 kg. Longevity is up to 39 years (Nowak, 1999).

|

Collared lemur at San Diego Zoo. |

|

Female collared lemur with male offspring (Duke University Primate Center). |

|

Male collared lemur at Duke University Primate Center. |

2) General Gestational Data

Barkley & Zelinski-Wooten (1998 ) give the length of gestation for ruffed lemurs as being 95 days. Doyle (1979) indicated a length of gestation for E. fulvus as 117 days with single young and rarely twins. Reproductive studies of any magnitude have only been done on black and ruffed lemurs (Bogart et al., 1977).

3) Implantation

Early embryonic/placental stages of these animals have not been described. Mossman (1987), however, suggested that implantation occurs in an antimesometrial location. The final seat of the diffuse singleton lemur placenta is one that extends throughout the bicornuate uterus.

4) General Characterization of the Placenta

As in the other lemurs studied, this was a diffuse, villous placenta that presumably occupied the entire bicornuate uterus. The nidation of lemur placentas is superficial (Mossman, 1987) and their placenta is epitheliochorial. There is a large allantoic sac but lemurs have no invasive trophoblast. This placenta was kindly made available by Dean Gibson of the Duke University Primate Center and comes from a near term delivery of a significantly autolyzed stillborn fetus weighing 55 g. Normal neonates weigh 75-85 g. The placenta weighed 6.353 g and measured 4 cm in greatest diameter and was 0.5 cm in thickness. The formalin fixed villous tissue was extremely pale. No cord was attached.

|

Opened placenta of brown lemur. |

|

Another view of this placenta. The black spots are embedded material from cage content. |

5) Details of fetal/maternal barrier

This placenta, like that of other lemurs, is typically epithelio-chorial with villi merely approximating the uterine epithelium. They are superficially attached to the undamaged uterine epithelium. The trophoblastic surface of villi is underlain by a dense capillary network and the capillaries often indent the very thin trophoblastic epithelium. Numerous macrophages (Hofbauer cells) and occasional leukocytes are found in the villous stroma. Because of the chorioamnionitis of this gestation and perhaps the postmortem changes in utero, there were leukocytes in the villous stroma and some bacteria were also present.

6) Umbilical cord

This specimen was not accompanied by an umbilical cord but it is suggested that it is likely to be similar to that of the ring-tailed lemur (see that chapter).

7) Uteroplacental circulation

I am not aware of any such studies.

8) Extraplacental membranes

A large allantoic sac was present in all specimens that is connected to the bladder by a wide allantoic duct of the umbilical cord. The allantois is lined by prominent cuboidal epithelium (see Benirschke & Miller, 1982, Fig. 1). Since this is a diffuse placenta, there are no free membranes. Thus, there is also no decidua capsularis.

9) Trophoblast external to barrier

There is no trophoblastic invasion of endometrium.

10) Endometrium

No typical decidua is formed.

11) Various features

No other relevant findings are reported.

12) Endocrinology

The only reference to possible placental gonadotropin production in lemurs I have been able to find indicates that ruffed lemurs ( Lemur variegates ) do not show gestational gonadotropin elevations (Barkley & Zelinski-Wooten, 1998 ). Circulating progesterone levels of cycles in Lemur catta and Lemur macaco have been published in papers by Bogart et al. (1977) and are summarized by Lasley et al. (1979). The three species examined by these investigators differ in length of cycles, seasonality and length of vaginal receptivity. No studies on brown lemurs were found in the literature. Urinary estrogens were monitored during pregnancy of ruffed lemurs by Shideler et al. (1983). Total urinary estrogen excretion rose significantly during gestation until they reached values 1,000 times of those at estrus. Estrone was the major secretory product.

13) Genetics

Lemur karyotypes vary considerably in chromosome number and structure as summarized by Rumpler (1975) and subsequent studies. Several investigators have made major contributions to our understanding of the taxonomic impact of these karyotypes as well as their significance for the fertility or infertility of the many hybrids that have been reported (Gray, 1972; Rumpler, 1975). We have had the good fortune of receiving tissues for karyotyping from the Duke Primate Center in North Carolina and found specimens of Eulemur fulvus collaris with chromosome numbers of 50, 51, and 52, while earlier this species was always judged to have 2n=52 only. Two such karyptypes are shown here and it will be seen that the difference is one Robertsonian fusion polymorphism. At least one female “hybrid” with 2n=51 has born offspring. This is of interest as some men with a single 13/14 translocation are infertile despite making trivalents at testicular meiosis (Gabriel-Robez et al., 1988). Gibson (in letters) writes that the karyotype with 2n=52 has the darkest collar, the karyotype 2n=50 has at times almost white collar and these may be located closest to L. f. albocollaris with 2n=48.

The studies on lemur hybrids by Ratomponirina et al. (1982) are of interest. They found that hybrids between L. fulvus (with 2n-60) and L.macaco (2n=44) occasionally resulted in fertile offspring, while those between L. fulvus collaris (2n=52) and L. macaco were sterile. They attributed this to defective spermatogenesis and showed biopsies of testes. Also, gonads of hybrids between L. fulvus (2n=60) and L. rubiventer (2n=50) had no germ cells. Hybrids between L. fulvus, L. collaris & L. albocollaris (2n=48) were always fertile.

14) Immunology

I am not aware of any studies.

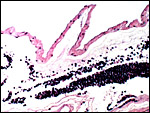

15) Pathological features

Chronic nephritis and pancreatic fibrosis were listed by Griner (1983) as causes of death in a brown lemur, but he had few specimens to study. I also do thus not know whether brown lemurs suffer the hemochromatosis that affects ruffed lemurs so commonly. An acute chorioamnionitis was found associated with the stillbirth. This is an uncommon condition in animals but a frequent cause of very severe prematurity in humans. There were bacilli both in the membranes and also in the villi.

|

Placental surface with marked acute chorioamnionitis (all the dark cells are pus). |

16) Physiologic data

I do not know of any physiological studies other than endocrine measurements.

17) Other resources

Fibroblast cell strains are available of a number of animals by contacting Dr. Oliver Ryder at CRES in the San Diego Zoo (oryder@ucsd.edu).

18) Other remarks – What additional Information is needed?

Details of early implantation especially are absent. More endocrine data are needed.

Acknowledgement

The animal photographs in this chapter come from the Zoological Society of San Diego. I appreciate also very much the submission of this placenta by Dean Gibson of the Duke Primate Center, NC.

References

Barkley, M. and Zelinski-Wooten , M.B.: Chorionic gonadotropins, Nonhuman mammals. In, Knobil, E. and Neill, J.: Encyclopedia of Reproduction. Vol. I, pp.601-614, 199 8 .

Benirschke, K. and Miller, C.J.: Anatomical and functional differences in the placenta of primates. Biol. Reprod. 26:29-53, 1982.

Bogart, M.H., Cooper, R.W. and Benirschke, K.: Reproductive studies of Lemur m. macaco, Lemur variegatus subcinctus and Lemur v. ruber . Internat. Zoo Yrbk. 17:177-182, 1977.

Bogart, M.H., Kumamoto , A.T. and Lasley, B.L.: A comparison of the reproductive cycle of three species of lemur. Folia Primatol. ( Basel ) 28:134-143, 1977.

Doyle, G.A.: Development and behavior in prosimians with special reference to the lesser bushbaby, Galago senegalensis moholi . In, Doyle, G.A. and Martin, R.D., eds.: The Study of Prosimian Behavior. Academic Press, NY, 1979, pp. 157-206

Gabriel-Robez, O., Ratomponirina, C., Cranz, C., Weill, A. Goldschmidt, P.A., Bollack, C. and Rumpler, Y.: Robertsonian heterozygosity and male sterility. Andrologia 20:463-466, 1988.

Gray, A.P.: Mammalian Hybrids. A Check-list with Bibliography. 2 nd edition.

Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux Farnham Royal, Slough , England , 1972.

Griner, L.A. : Pathology of Zoo Animals. Zoological Society of San Diego , San Diego , California , 1983.

Lasley, B.L., Bogart, M.H. and Shideler, S.E.: A comparison of lemur ovarian cycles. Chapter 31, pp. 417-424, in: N.J. Alexander: Animal Models for Research on Contraception and Fertility. Harper & Row, Hagerstown , 1979.

Mossman, H.W. and Duke, K.L.: Comparative Morphology of the Mammalian Ovary. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison , Wisconsin , 1973.

Nowak, R.M.: Walker 's Mammals of the World. 6 th ed. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1999.

Ratomponirina, C., Andrianivo, J. and Rumpler, Y.: Spermatogenesis in several intra- and interspecific hybrids of the lemur ( Lemur ). J. Reprod. Fert. 66:717-721, 1982.

Ratomponirina, C., Andrianivo, J. and Rumpler, Y.: Spermatogenesis in several intra- and interspecific hybrids of the lemur (Lemur). J. Reprod. Fert. 66:717-721, 1982.

Rumpler, Y.: The significance of chromosomal studies in the systematics of the Malagasy lemurs. Pp. 25-40, in, I.Tattersall and R. W. Sussman, eds.: Lemur Biology. Plenum Press, NY, 1975.

Puschmann, W.: Zootierhaltung. Vol. 2, Säugetiere. VEB Deutscher Landwirtschaftsverlag Berlin , 1989.

Shideler, S.E., Czekala , N.M. , Benirschke, K. and Lasley, B.L.: Urinary estrogens during pregnancy of the ruffed lemur ( Lemur variegatus ). Biol. Reprod. 28:963-969, 1983.

Simons, E.L. and Rumpler, Y.: Eulemur : new generic name for species of Lemur other than Lemur catta. Compt. Rend. Acad. Sci. Paris, ser.3, 307:547-551, 1988.

Tattersall, I. : Speciation and morphological differentiation in the genus Lemur . Pp. 163-176, in Kimbel, W.H. and Martin, L.B., eds. Species, Species Concepts, and Primate Evolution. Plenum Press, NY 1993.