|

(Clicking

on the thumbnail images below will launch a new window and a larger

version of the thumbnail.)

|

Castor canadensis

Order: Rodentia

Family: Castoridae

1) General Zoological Data

There are two species of beaver, the Canadian/American Castor canadensis and Castor fiber, the Eurasian species. "Castor" is the Greek word for beaver (Wilson & Reeder, 1992). Some authors have considered these species to be one and the same, but Lavrov & Orlov (1973) have drawn a distinction between them. They showed that C. fiber possesses 48 rather than the 40 chromosomes of the Canadian beaver. The Canadian/American beaver varies greatly in size from region to region, this being one reason why numerous subspecies have also been assigned. The same is true of the Eurasian species.

The rodent family Castoridae has an uncertain ancestry, a feature that is discussed in some detail by Romer (1966). Thenius & Hofer (1960) also supported the notion that the true ancestry of beavers is still debated and related in their book that beavers had once been of bear-like size, in the Pleistocene.

A detailed review of the animal's biology is found by Rue (1964). It states that the beavers live 12 years in the wild but may attain at least 19 years in captivity. The beavers are said to continue growing throughout their life. It is difficult to determine sex as, externally, the animals are very similar. Radiologically, the baculum can be visualized in adults (Puschmann, 1989).

Beavers weigh up to 45 kg; males are usually as big as females. Animals been found, however, that were much heavier. Additional and specialized anatomical data may be found in Hayssen et al. (1993). The most notable features, of course, are the webbed feet and the extraordinary tail of beavers, both adaptations to their aquatic environment. The aquatic adaptation also makes it more difficult to keep beavers in captivity and thus they are not often seen in zoological parks. Beavers are monogamous and the newborn Canadian beavers weigh between 360 and 700 g according to numerous studies listed by these authors. There are between 2 and 8 offspring, but 3-4 appears to be most common.

|

Canadian beaver female, courtesy of Andy Karabatsos, San Diego. |

|

Canadian beaver, courtesy of Andy Karabatsos, San Diego. |

|

Beaver skull of a 28 kg male animal from Vermont. |

The length of gestation is estimated to be around 100 days, and was given as being between 90 and 128 days by some authors. Litter size is usually 3-4 pups. Newborns weigh around 500 g. There is one litter per year and the animals have a distinctly seasonal cycle.

3)

Implantation

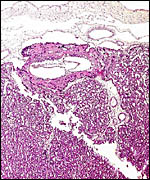

Implantation is superficial and commences antimesometrially with the disk

ultimately occupying a mesometrial location. There then develops an incompletely

inverted yolk sac placenta and a disc composed of the labyrinth with a

hemodichorial fetal/maternal barrier, according to the classification

of Enders (1965). Early stages with the implantation cone have been described

by Fischer (1971) and were also illustrated by him in several diagrams.

The remarkable feature in the implantation of the beaver blastocyst is

that it occurs over an endometrial "papilla". This feature may

be responsible for the unusual creation of a large "subplacenta"

in the beaver placenta that differs markedly from other rodent placentas.

4)

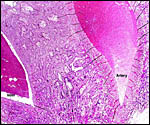

General Characterization of the Placenta

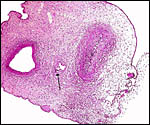

This placenta was kindly made available by Matthew Heflin of the University

of Minnesota. It came from the Minnesota Zoological Garden from the birth

of one of four pups and was found floating in the water. The placenta

weighed 60 g, had a split umbilical cord to which the membranes were attached.

The measurements are shown in the next photograph. Although it was fixed

quickly in formalin after retrieval, some degree of autolysis is present,

especially of the epithelium of the membranes.

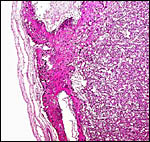

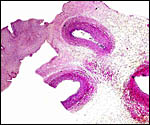

The placenta is thick, large and has a "reniform" shape, as

has been pointed out by Mossman (1987) and as was also referred to in

the excellent descriptions by Fischer (1971, 1985). It has a large basal

region that is referred to as "subplacenta". Mossman (1987)

pointed out, however, that this region is probably not homologous to the

subplacenta of the hystricognath rodents. Indeed, the term "subplacenta"

has been questioned. Suffice it to say, that a large labyrinthine and

smaller lower (sub-) placenta are obvious when the placenta is sectioned.

The subplacenta is shed with the placenta and is detached from the decidua,

as was pointed out already by Fischer (1971). This is an inverted yolk

sac placenta with the yolk sac membranes attaching circumferentially at

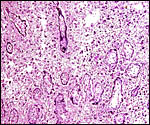

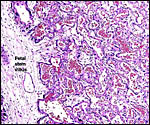

the site where subplacenta and labyrinth meet. The labyrinth is supplied

by two large maternal arteries that enter laterally from the decidua,

and it is drained by a large central vein. Both are easily seen macroscopically

as being located in the subplacenta. There is an abundance of peripheral

trophoblastic giant cells that derive from the bilaminar omphalopleure.

A relatively small allantoic sac lies above the disk, but I have not been

able to identify an allantoic duct with certainty. There was, readily

identified, the brown inverted yolk sac membrane that attached laterally

to the disk at about the junction of subplacenta and labyrinth. The major

features of this placenta are shown diagrammatically in the modified copy

of Mossman's table 18.

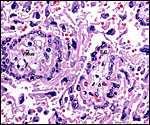

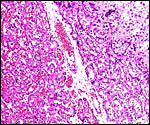

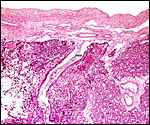

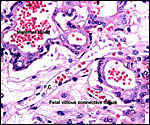

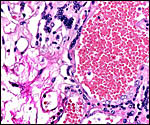

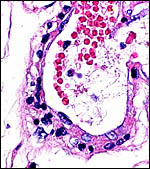

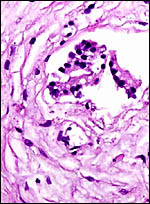

Fischer's study of the subplacenta is really the most exhaustive and descriptive (1985) of this complex organ. He described it as comprising 1/3 of the total mass and having detached spontaneously from the underlying decidua basalis at birth, and as being traversed by two maternal arteries and a central vein. The arteries are markedly altered by trophoblastic destruction of their arterial walls, similar to what is observed in primates. The subplacenta, he suggested, contains villous structures that much resemble the villi of primate placentas as well. These villi of the subplacenta are depicted below. These villi contain loose connective tissue and thin-walled fetal capillaries, and they are covered by trophoblast. Fischer suggested that this is composed of an inner layer of cytotrophoblast and outer layer of syncytium. This was not always evident in my sections and the "barrier" may require future electronmicroscopy. Remarkably though, around the villi lie a profusion of ill-defined cells. There are maternal red blood cells (sometimes in larger pools), mononuclear cells (with much glycogen) and, Fischer stated, many pigmented cells that fail to give an iron staining reaction. (Note though that he did describe iron-positive reactions in the brown inverted yolk sac epithelium. See further discussion on the nature of the pigment in the chapters on Alpine Ibex and Nilgiri Tahr). Fischer also did not observe red cell phagocytosis. My placenta did not have any pigment at this location but the yolk sac epithelium had macroscopically the brown color of iron pigment. Apparently there is no explanation for the existence of the maternal red cells in the subplacenta and there is also no venous drainage of this region. Nevertheless, despite the lack of draining vessels, stagnation and fibrin deposits have not been seen here. Mossman (1987) urged that the blood supply of this placental region be studied by injection, as it may be partially supplied by the yolk sac vasculature. The "raison d'?tre" for this structure, the subplacenta, is ambiguous and, as Fischer (1985) pointed out, its construction is so different from that of the subplacenta of hystricomorpha, that only the name applied ("subplacenta") is synonymous. Mossman (1987) was also puzzled by this peculiarity and suggested that, otherwise, the placenta is more like that of sciuromorph rodents that the hystricomorphs.

6)

Umbilical cord

The cord is split (probably because of disruption of the membranes after

delivery) into the major and thicker labyrinth-related portion (14 cm

long) with two arteries and one vein, and the thinner inverted yolk-sac-related

(10) portion that contains a pair of vessels and the remnants of a duct.

There was no spiraling.

There have been no studies to give information on the maternal vasculature and physiology of the placental circulation. Indeed, as Mossman (1987) has pointed out, these studies are badly needed to understand the complexity, especially that of the subplacenta. The placenta I was able to examine had no maternal endometrial tissue attached; nevertheless, the uterine arterial branches that run through the subplacenta were modified by invading trophoblast and one may expect it to travel more proximally as well.

8)

Extraplacental membranes

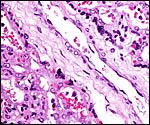

There is an inverted yolk sac membrane that attaches to the endometrium

and bears a villous cover. It is brown and pigmented with iron-containing

deposits (Fischer, 1985). Presumably it has an absorptive function. The

amnion develops by folding and is covered by a very thin, flat epithelium

that lacks squamous metaplasia and verrucae.

|

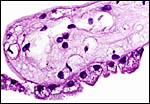

Surface vitelline epithelium of membranes with autolysis from exposure to water. |

No judgment can be made how deeply the trophoblast infiltrates the decidua basalis, as this has not been described in the very few studies of beaver placentas. It is clear, however, that the maternal arteries that course through the subplacenta are infiltrated and modified by trophoblast. Perhaps this extends further into the uterus.

10)

Endometrium

The beaver has a Y-shaped bicornuate uterus. Fischer (1971) described

the significant endometrial changes that take place with early implantation.

The endometrium becomes very vascular in early stages of pregnancy and

then develops into decidua. In the endometrium of term placentation, however,

there is "no trace of uterine epithelium" in the antimesometrial

uterine wall. A mass of extravasated blood is here found. The yolk sac

villi of the vascular splanchnopleure are located in the blood and, consequently,

have a brownish color in the delivered placenta. No decidua capsularis

ever develops.

11)

Various features

The striking subplacenta of this and some other rodents has been discussed

in greater detail above. For additional discussion see also Fischer (1985).

He believed it to be a "fetal organ" and perhaps related to

gonadotropin production and having an absorptive quality. At least, contrary

to the views expressed for the guinea pig, the area was not construed

to be a zone of growth, and it remained to term.

12) Endocrinology

I have been unable to find any literature on beaver endocrine studies.

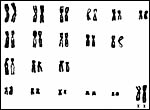

13)

Genetics

The Canadian beaver has 40 chromosomes (Hsu & Benirschke, 1968; Lavrov

& Orlov, 1973; Genest et al., 1979). The latter authors added G-and

C-banding to their chromosomal study and made some corrections of the

arrangements suggested earlier. Kuehn et al. (2000) employed mtDNA from

hair bulbs for the differentiation of American and Eurasian beavers. I

am not aware that hybrids have been described between these two species

of Castoridae. Moreover, the fact that Castor fiber has 48 chromosomes

according to Lavrov & Orlov, 1973) makes it less likely that they

hybridize, at least fertilely.

|

Karyotype of male beaver from Vermont. |

|

Karyotype of female beaver from Vermont. |

I am unaware that any studies have been done.

15)

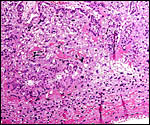

Pathological features

Giardiasis is said to be transmitted often from beavers that harbor the

cysts (Dykes et al., 1980; Wallis et al., 1984; Monzingo & Hibler,

1987). Smith & Frenkel (1995) found Toxoplasma gondii in only

one beaver and concluded that Toxoplasma carriage was principally a problem

for carnivores. Some beavers may harbor the bacteria that cause tularemia

(Morner, 1992). Sileo & Palmer (1973) found protothecosis (an algal

infection) in a beaver.

Anderson et al. (1989) reported a follicular thyroid carcinoma in an 11

year old beaver that died with diarrhea; the latter was believed to have

been caused by parvovirus infection. Interstitial nephritis appears to

be common in beavers. Stuart et al. (1978) have studied this in numerous

specimens, and it has also been observed in our zoo from animals brought

for autopsy from outside personnel. The cause is not fully understood.

16)

Physiologic data

Much information is available on various aspects of the beaver physiology.

For instance, Swain et al. (1988) found the heart rate to increase with

swimming and diving, and that it was low when sleeping and resting. The

effects of anesthesia were recorded by Greene et al. (1991). Kakela &

Hyvarinen (1996) studied the differences of fatty acids in the extremities

of beavers and muskrats. Later (Kakela et al., 1996) defined the unusual

fatty acids in the depot fat of the beaver. Carlson & Welker (1976)

investigated various anatomical and behavioral specializations, especially

those of the tail in beavers.

17)

Other resources

Regrettably, we have no cell lines at CRES

and if anyone can supply biopsies to establish a tissue culture, this

would be appreciated.

18)

Other remarks - What additional Information is needed?

It would be nice to see some study of the attached placenta to ascertain

how deeply the arterial trophoblast infiltration reaches into the uterus.

As Mossman (1987) has pointed out, a study of the blood supply to the

various regions of the disk and subplacenta is needed. Endocrine studies

are also needed. Additional cytogenetic and placental studies of Castor

fiber, the Eurasian beaver, are desirable, to include banding or FISH

study of the chromosomes.

Acknowledgement

The placenta was graciously collected and made available by Matthew Heflin

who was serving an externship at the Minnesota Zoological Garden while

a senior veterinary student of the University of Minnesota. The animal

photographs in this chapter were kindly donated by Mr. Andy Karabatsos

of REACTOR, San Diego, CA 92121, 4445 Eastgate Mall.

References

Anderson, W.I., Schlafer, D.H. and Vesely, K.R.: Thyroid follicular carcinoma

with pulmonary metastases in a beaver (Castor canadensis). J. Wildl.

Dis. 25:599-600, 1989.

Carlson, M. and Welker, W.L.: Some morphological, physiological and behavioral specializations in North American beavers (Castor canadensis). Brain Beh. Evol. 13:302-326, 1976.

Dykes, A.C., Juranek, D.D., Lorenz, R.A., Sinclair, S., Jakubowski, W. and Davies, R.: Municipal waterborne giardiasis: an epidemiologic investigation. Beavers implicated as a possible reservoir.

Enders, A. C.: A comparative study of the fine structure of the trophoblast in several hemochorial placentas. Amer. J. Anat. 116:29-68, 1965.

Fischer, T.V.: Placentation in the American beaver (Castor canadensis). Amer. J. Anat. 131:159-184, 1971.

Fischer, T.V.: The subplacenta of the beaver (Castor canadensis). Placenta 6:311-321, 1985.

Genest, F.B., Morisset, P. and Patenaude, R.P.: The chromosomes of the Canadian beaver Castor canadensis. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 21:37-42, 1979.

Greene, S.A., Keegan, R.D., Gallagher, L.V., Alexander, J.E. and Harari, J.: Cardiovascular effects of halothane anesthesia after diazepam and ketamine administration in beavers (Castor canadensis) during spontaneous or controlled ventilation. Amer. J. Vet. Res. 52:665-668, 1991.

Hayssen, V., van Tienhoven, A. and van Tienhoven, A.: Asdell's Patterns of Mammalian Reproduction: a Compendium of Species-specific Data. Comstock/Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1993.

Hsu, T.C. and Benirschke, K.: Atlas of Mammalian Chromosomes. Vol. 2, Folio 59, 1968. Springer-Verlag, New York.

Kakela, R. and Hyvarinen, H.: Fatty acids in extremity tissues of Finnish beavers (Castor canadensis and Castor fiber) and muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus). Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 113:113-124, 1996.

Kakela, R., Hyvarinen, H. and Vainiotalo, P.: Unusual fatty acids in the depot fat of the Canadian beaver (Castor canadensis). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 113:625-629, 1996.

Kuehn, R., Schwab, G., Schroeder, W. and Rottmann, O.: Differentiation of Castor fiber and Castor canadensis by noninvasive molecular methods. Zoo Biol. 19:511-515, 2000.

Lavrov, L.S. and Orlov, V.N.: Karyotypes and taxonomy of modern beavers (Castor, Castoridae, Mammalia). Zoologicheskii Zhurnal 52:734-742, 1973 (In Russian; English abstract).

Monzingo, D.L. and Hibler, C.P.: Prevalence of Giardia sp. in a beaver colony and the resulting environmental contamination. J. Wildl. Dis. 23:576-585, 1987.

Morner, T.: The ecology of tularaemia. Rev. Sci. Tech. 11:1123-1130, 1992.

Mossman, H.W.: Vertebrate Fetal Membranes. MacMillan, Houndmills, 1987.

Puschmann, W.: Zootierhaltung. Vol. 2, Säugetiere. VEB Deutscher Landwirtschaftsverlag Berlin, 1989.

Romer, A.S.: Vertebrate Paleontology. University of Chicago Press, 1966.

Rue, L.L. III: The World of the Beaver. J.B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia, 1964.

Sileo, L. and Palmer, N.C.: Probable cutaneous protothecosis in a beaver. J. Wildl. Dis. 9:320-322, 1973.

Smith, D.D. and Frenkel, J.K.: Prevalence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in wild mammals of Missouri and east central Kansas: biologic and ecologic considerations of transmission. J. Wildl. Dis. 31:15-21, 1995.

Stuart, B.P., Crowell, W.A., Adams, W.V. and Morrow, D.T.: Spontaneous renal disease in beaver in Louisiana. J. Wildl. Dis. 14:250-253, 1978.

Swain, U.G., Gilbert, F.F. and Robinette, J.D.: Heart rate in the captive, free-ranging beaver. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A: 91:431-435, 1988.

Thenius, E. and Hofer, H.: Stammesgeschichte der Säugetiere. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1960.

Wallis, P.M., Buchanan-Mappin, J.M., Faubert, G.M. and Belosevic, M.: Reservoir of Giardia sp. in southwest Alberta. J. Wildl. Dis. 20:279-283, 1984.

Wilson D.E. and Reeder, Eds.: Mammal Species of the World. Second Ed. Smithsonian Inst. Press, Washington, DC, 1992.